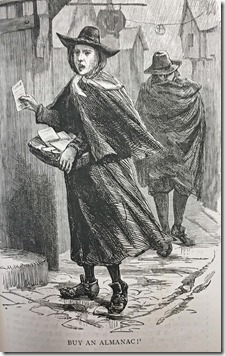

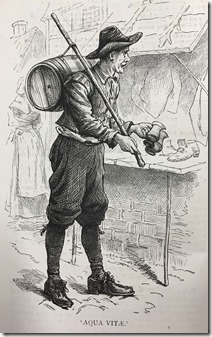

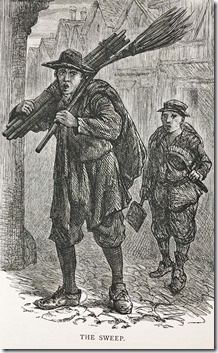

The final part of Street Criers of London, copied from the 1895 editions of the Hawes Parish magazine reproduced here with the kind permission of Hawes Parochial Church Council.

In the Hawes Parish Magazines there were no accreditations or dates provided. Within some of those below there is a bit of a guide to dates. The text is as printed in those magazines and I have added some dates.

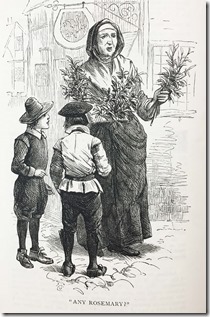

Any Rosemary

The cry of ‘Rosemary and Lavender’ was a very common one in the streets and alleys of Old London. The leaves have a fragrant and pungent smell. It is said to relieve headache. In the country it is valued by many a villager and, with its companion lavender, is used to sweeten linen drawers and cupboards.

The cry of ‘Rosemary and Lavender’ was a very common one in the streets and alleys of Old London. The leaves have a fragrant and pungent smell. It is said to relieve headache. In the country it is valued by many a villager and, with its companion lavender, is used to sweeten linen drawers and cupboards.

As late as Hogarth’s time it was common to use rosemary at funerals. It is ever green and so was regarded as an emblem of the immortality of the soul. In an obituary preserved among the Sloanian MSS in the British Museum there is the following entry:

‘Jan. 2.1671 – Mr Cornelius Bee, Bookseller, in Great Britain, died. Buried Jan. 4 at Great St Bartholomew’s without sermon, without wine or wafers; only gloves and rosemary.’ Mr Gay, when describing the funeral of a certain Blowsenda, records, ‘Sprigged rosemary the lads and lasses bore.’

In Cartwright’s Ordinary, an old play, we read: ‘If there be any so kind as to accompany my body to the earth, let them no want for entertainment: pray thee let them have a sprig of rosemary dipped in common water.’

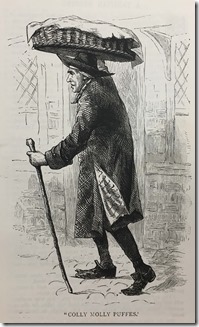

Addison, in the Spectator, nearly two hundred years ago, speaks of the ‘Colly Molly puff-man’, so that he is a sort of historical character. He has sold puffs and tarts, which were widely known, or Addison would not have spoken of them. The bakers’ shops have now taken the trade from the street vendors of pastry, though we sometimes in summer see a man treading the gutter of the crowded Strand with a tray of cakes balanced on his head, but he does not make any musical appeal for customers.

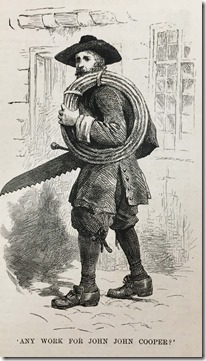

Any Work for John Cooper?

Beer was more used in the old days than even at present, for it was used at breakfast where we use tea and coffee. In those days barrels of beer and casks of wine were more common in the cellars of London citizens than they are now, and worn out and damaged casks must have made plenty of work for John Cooper.

His cry, as we read in old books, was ‘not without harmony’ and he used to ‘swell the last note with a hollow voice’. Sometimes he added to his cry:

‘Work for the cooper? Maids, give ear!

I’ll hoop your tubs and pails!’

In the Bridgewater Library, belonging to the Earl of Ellesmere, there is a series of thirty-two curious engravings on ‘The Manner of Crying Things in London’. The date is certainly before 1680 for the title is written by the second earl who died in that year. Amongst the thirty-two, one is ‘Worke for a Cooper’, so that this workman used to traverse the streets two hundred years ago.

It was almost the rule in the old times to hail a man by his trade, so that Will Baker and Tom Butcher were no surnames, but callings, and when the man called out ‘Any work of John Cooper?’ he meant as we should say, John the Cooper. It is thus that we have got many of our common surnames. Baker, Butcher, Cooper, Smith are only samples out of a list of names which it may amuse our readers to make for themselves.

Old Bellows

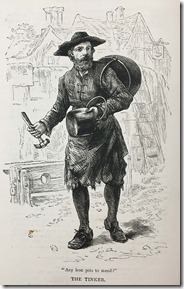

In the olden days the craftsman did not sit in his shop and wait for work to be brought to him. He went out and proclaimed along the streets his readiness for a job in a more or less musical cry. We have seen ‘John Cooper’ on his rounds; now we see the smith, with his hammer in hand and his pincers in his girdle, ready to mend any old bellows which had got worn out by puffing at the fire of wood or coal. The shape of bellows does not seem to have changed much in these hundred years. The bellows which our smith carries has about the same shape as the dainty little painted bellows which we sometimes see hanging beside the chimneypiece in a lady’s drawing room. The mechanism too is just the same as we see on a large scale in the forge of the village smithy. A poet says of the blacksmith:

‘The smith prepares his hammer for the stroke,

While the lunged bellows hissing fire provoke.’

The action of the bellows is not unlike that of our lungs: so we sometimes hear a man say, ‘I have fine bellows,’ meaning good lungs. What we call blowing in one case we call breathing in the other.

The bellows-mender in our picture looks as if he had a good pair of lungs and could sing out lustily the couple of his trade:

‘Old bellows to mend – old bellows to mend?

An honester workman none could send.’

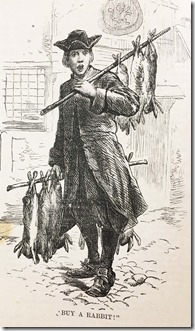

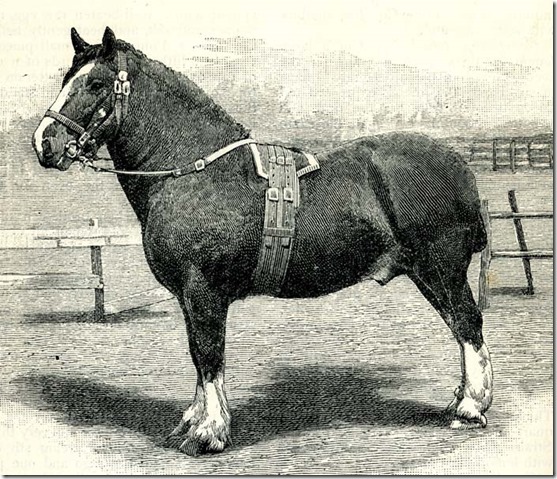

Buy a Rabbit! – Rabbit!

A hundred years ago the hawker of rabbits most likely had bought them from the man who had snared or shot them, if he had not killed them himself. A man might then have had some hours in Essex forests or on the Surrey commons, and then walked back to the streets to sell the rabbits he had bagged. Nowadays rabbits are still sold in the streets, though the hawker generally has a cart or a long barrow. His rabbits come up by rail from the country, where there are not only wild rabbits, but also rabbit warrens where thousands are reared.

It is said that, besides English rabbits, two hundred tons of rabbits are imported annual from Ostend. These are sent over without the skins, which are half as valuable as the flesh.

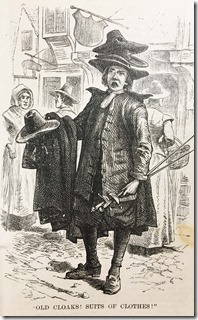

Old Cloaks! Suits of Clothes!

In old, as in modern times, there has always been opposition to the street vendor. As far back as Queen Elizabeth’s reign an effort was made to ‘keep hucksters, pedlars and hagglers out of the open streets’. In the time of Charles I they were described as unruly people. In 1694 stringent rules were enacted, threatening them with the terrors of the law then in force against ‘rogues and sturdy beggars’. The least penalty for breaking these laws was a severe whipping; the reason was honestly given, because citizens and shopkeepers wished it believing these poor folk injured their trade.

But in spite of opposition the street traders continued. Dr Johnson in the Adventurer says ‘the attention of a new-comer in London is generally struck by the multiplicity of cries which meet him in the street’. Among these one of the oldest was that of ‘Old clowse’ and ‘Old clo’ ‘ – still familiar in our day. The pictures of the ‘Old clo’ ‘ man in former days generally give him with three or more hats, one above the other, on his head.

One hundred years ago the ‘old clo’ ‘ man did not limit himself to buying, he also sold and exchanged; and so in our illustration, which is from an old book, the huckstar is also selling swords and rapiers!

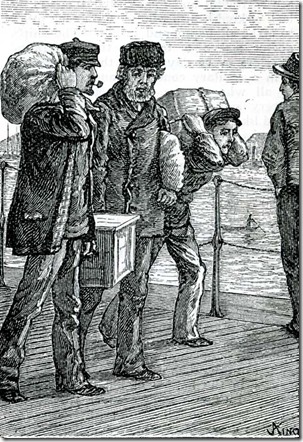

Old Raree Show

The ‘raree showman’ made his living in old days chiefly out of the youngsters. When he had a good gang of boys at his heels he chose a likely spot, and put on the ground his box, which was really a cage. He would prop up the end on a stick so that the boys might better see his show. It would consist of such animals as rabbits, hedgehogs, white mice and perhaps a snake or two. These were taught to do some little tricks which interested the children. There were street shows of another kind – the puppet show which attracted older folk.

In the time of Queen Anne it was quite an institution frequented by persons of quality. One was set up in the piazza of Covent Garden and the ringers of St Paul’s Cathedral complained to the Spectator that, when the bell was rung for daily morning prayer, people seemed to think that it was invitation to the puppet show.

We have our puppet show of the present day which rarely fails to attract a crowd. When the light framework of Punch is set up with the squeaking performer and the meek dog Toby there is soon a crowd to enjoy the ferocious drama, which may be of Italian origin, but which certainly now belongs to the London streets and delights our youngsters as did the raree show of long ago.

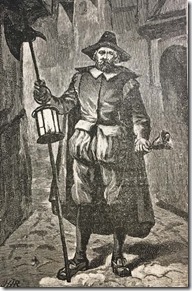

The Watchman

The street watchman of hundred years ago looked dignified but he was of little use as a protector of the public. One of his chief duties was to compel citizens to contribute to the lighting of the streets by suspending horn lanterns outside their houses. Many tried to evade the law to save the cost.

In 1416 Sir Henry Barton, mayor, ordered lanterns and lights to be hung out on winter evenings between All Hallows and Candlemas. This gave rise to the watchman’s cry: ‘Lant-horns and a whole candle! Hang out your light!’ Some thrifty folk only put a small piece of candle in the lanterns, hence the cry, ‘A whole candle’. The watchman would sometimes cry his warning in verse:

‘A light here, maids; hang out your light,

And see your horn be clear and bright,

That so your candle clear may shine,

Continuing from six to nine,

That honest men that walk along

May see to pass safe without wrong.’

The horn to be ‘clear and bright’ referred to the lantern sides which were filled with horn, not glass.

A mayor in Queen Mary’s time [reigned 1553-1558], who manifestly had no thought for the weary citizen’s sleep after a hard day’s toil, provided the watchman with a bell and, with this dingdong accompaniment, he shouted his verses down to the time of the Commonwealth [1649-1660].

About this period we find the watchmen also called bill-men. This bill, like an axe on a pole was, in case of fire, to be used amongst the portions of wooden houses in danger of burning, and to chop a breach between the burning part and the endangered parts, a needed precaution with the dangerous buildings of long ago.

The watchman by-and-by came to be called ‘Old Charley’ and was a venerable person, bearing in his hands the halberd and horn lantern. Many of these should have been in an almshouse. They were laughed at and derided. Their night cries were doleful, and the ringing bell and the cry, ‘Just gone twelve and a starry night’ or ‘Past four and a rainy morning’ drove away sleep from many a weary man and woman. To guard ‘Charley’ from rain and snow, he was provided with a sentry box. It was a favourite prank with the young ‘bloods’, as they were called of the Regency [1811-1820], if they found Charley asleep in his box, to steadily overturn it and leave the old fellow a prisoner beneath it until some passer-by released him.

This system of protecting the citizens continued till 1829 when Sir Robert Peel’s Act brought in the present metropolitan police, known to us as ‘Bobbies’ or ‘Peelers’, so nicknamed from Sir Robert Peel. Certainly our modern guardian in his neat uniform, with his drill, strength and trained intelligence, is a great improvement on the infirm ‘Old Charley’ of bygone times.