In the March and April 1900 editions of the Church Monthly the Rev Theodore Wood wrote about some interesting parasitic activity – such as that of oil beetles (see Editor’s note below) and stylops.

Rev Wood:

March is a month of which many hard things have been said; and certainly in some seasons it affords us little else than a second edition of winter in an aggravated form. Yet it seldom comes to an end without bringing us a few fine sunny days, when birds are singing and butterflies flitting to and fro, and the breath of spring is in the air. It is a pleasure merely to be alive. And everywhere Nature is as busy as she can possibly be, fresh with the vigour gained from her long winter sleep, and straining every nerve in preparation for the bright and active season that lies before her.

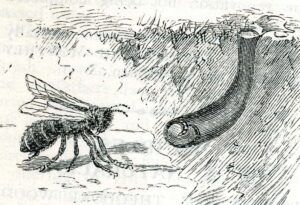

Do you see those small round holes in the trodden path, each with a tiny pile of crumbled mould around it? Watch one of them for a little while, and you will see a bee come out – a little grey-brown bee, with a round, hairy body and rather short wings. It is a solitary bee (right – from Church Monthly) which is usually engaged in sinking its burrow. It makes no comb; it secretes no wax; it stores up no honey. It just digs a perpendicular tunnel, some eight or ten inches in depth, and then hollows out a few small cells at the bottom. In each of these cells it lays an egg and places a store of provision. Sometimes this provision consists of pollen worked up into ‘bee bread’. For solitary bees do not tend their young as hive and humble bees do. They provide for them once and for all, before they hatch out from the egg-shell; and after that they never visit them again.

Do you see those small round holes in the trodden path, each with a tiny pile of crumbled mould around it? Watch one of them for a little while, and you will see a bee come out – a little grey-brown bee, with a round, hairy body and rather short wings. It is a solitary bee (right – from Church Monthly) which is usually engaged in sinking its burrow. It makes no comb; it secretes no wax; it stores up no honey. It just digs a perpendicular tunnel, some eight or ten inches in depth, and then hollows out a few small cells at the bottom. In each of these cells it lays an egg and places a store of provision. Sometimes this provision consists of pollen worked up into ‘bee bread’. For solitary bees do not tend their young as hive and humble bees do. They provide for them once and for all, before they hatch out from the egg-shell; and after that they never visit them again.

What is this great bluish-black beetle, with tiny wing-cases and a huge, clumsy body which its short little limbs can scarcely drag over the ground?

It is an oil beetle and we have only to pick it up to learn the reason for its title; for as we do so a yellow, evil-smelling, oil liquid oozes out from the joints of its legs. In some parts of the country, strange to say, this liquid is regarded as a specific for rheumatism.

The beetle is on its way to lay its eggs. There are many thousands of these, and it lays them in holes in the ground – four or five thousand, perhaps, in a single hole. In a few days’ time they hatch, and out of each comes a little tiny black grub with six very long legs. Led by some strange instinct, these grubs make their way at once to flowers which [solitary] bees are likely to visit. Then they climb the stems and hid in the blossoms till a bee appears, when they cling to its hairy body, and so are carried back by it, all unknowingly, to its nest. There they live out the rest of their lives, eating both the eggs and the stores which have been supplied for the latter for food.

Notice the blind-worm gliding through the grass. It is not a snake, although it looks like one and behaves like one. It is not blind, in spite of its name, for it has pair of sharp little black eyes. Neither is it a worm. It is a legless lizard, perfectly harmless, which has been lying torpid throughout the winter, and is now engaged in searching for the tiny white slugs upon which it feeds. We will not handle it, for it is a timid creature, and is given to protect itself, in moments of danger, by snapping off its own tail! The severed member, the nerves of which are evidently highly irritated by this strange mutilation, instantly becomes endowed with singular vitality, and begins to leap and twist about as though possessed of independent existence. And meanwhile, as one’s attention is occupied in watching its antics, the blind-worm creeps away to a place of safety, and there proceeds to grow a new tail.

April

It is something to be thankful for that, even in these days of excursions and cheap trips, there are still spots of ideal beauty which are seldom trodden by the foot of man. Let us ramble through a lonely glen, hidden away among the hills, where Nature reigns unmolested, and beasts and birds and insects dwell in utter security. Its sloping sides are brown with last year’s bracken and green with feathery moss. Here and there are patches of yellow, where primroses cluster together. Under the trees are anemones with their delicate pencilled blossoms and starworts with petals widely expanded.

It is something to be thankful for that, even in these days of excursions and cheap trips, there are still spots of ideal beauty which are seldom trodden by the foot of man. Let us ramble through a lonely glen, hidden away among the hills, where Nature reigns unmolested, and beasts and birds and insects dwell in utter security. Its sloping sides are brown with last year’s bracken and green with feathery moss. Here and there are patches of yellow, where primroses cluster together. Under the trees are anemones with their delicate pencilled blossoms and starworts with petals widely expanded.

Did you see that bird dart down the stream – a passing flash of black and white? It was a dipper, and there he is, sitting on a mossy stone in the midst of the water, not twenty yards away. Never was bird more aptly named for, as we watch, he “dips” now and again, and yet again as if he were a little country school-maid curtseying as she meets the parson. He is just like a magnified wren with a white waistcoat. He has just the same jerky movements and just the same little upturned tail. Now he is searching amongst the moss for the little yellow-spotted beetles which hide there. The next moment he has plunged into the water and is hunting for snails and grubs at the bottom. Then, once more, the black-and-white streak flashes past us. He has darted up stream again to join his mate, who is dipping and diving a hundred yards away. (Photo taken at Aysgarth Falls copyright Pip Pointon)

The air is full of the hum of bees. That is because a sallow bush is growing by the side of the water and every branch is laden with golden catkins. There are hive bees from the cottage garden at the foot of the glen, and red-hipped humble-bees from many a moss-covered hollow in the ground, and solitary bees. Most are intent on draining the honey-laden blossoms of their juices for the hungry little ones at home.

But there is a tragedy. One of the bees is weak on the wing. It settles and we examine it and see the reason why. A little white object is projecting from between the segments of its abdomen. That white object is head of a stylops. It stays there and never comes out, and feeds incessantly on the juices of the bee’s body! The ways of parasites are strange. They cling to the lower surface of the beetle’s body; they live inside caterpillars and feed upon their fat; they cause great swellings on the backs of cattle; and they drive even the elephant himself half mad with the torment of their bites. But the ways of this parasite are quite the strangest of all.

The male is an evident beetle with large milk-white wings and odd little branched antennae. But the female, practically speaking, never becomes more than a grub. In the bee’s body she lives; and in the bee’s body she dies.

The glen is full of life – animal life, bird life, reptile life and insect life. It is a panorama of natural beauty as we ramble through it, and a cyclopaedia of natural wonders when we pause to search out its secrets. We might come daily for a week, a month, or a year and not exhaust them all.

Editor’s note:

I like to check the latest reports concerning the creatures that the Rev Wood recorded. There is often more up-to-date information and this is especially true of his account about stylops. He believed the female stylops had its head inside a bee’s abdomen, whereas now it is now that the head is sticking out. So I have slightly edited his account.

It was also sad to learn that since he wrote about oil beetles it is likely that three of the UK’s native ones have become extinct. For more about that see:

https://cdn.buglife.org.uk/2019/08/Oil-Beetle-national-survey-leaflet-for-web_5-species.pdfhttps://www.coleoptera.org.uk/meloidae/home

The Rev Wood’s articles in the Church Monthly are reproduced with the kind permission of Aysgarth Parochial Church Council.