It was the headline that caught my attention: ‘Working Men and Poultry Keeping’. During the last decade of the 19th century several articles by the editor of Fowls, the Rev G.T.Laycock, were published in The Church Monthly.

He obviously admired the men who raised chickens in their backyards: ‘The backyard poultry keeper is invariably a man of resource. He has learnt what thousands of country cottagers have yet to learn – how to make the best use of his outdoor opportunities. How ingenious are his contrivances; how excellent his plans for economising space. Everything seems against him, and yet by care, attention and ingenuity he surmounts all difficulties and his fowls in their appearance and productiveness are his reward.’ (1895)

In an article in 1892 he wrote: ‘Many of those who habitually gaze upon smiling fields and picturesque landscape would be utterly astounded could they behold many a working man’s poultry yard in the midst of a busy town. A flagged floor instead of greensward, and walls fifty feet high in place of hedgerows. Everything against him, in fact, but one – the keen interest of the owner and a fixed determination to succeed against all odds. And many do succeed.

‘The fowls that denizen such yards are not the puny, washed-out looking creatures most would think. The egg record is pretty sure indicator of a healthy state and many a town dweller’s egg record, when compared with that of his country cousin, knocks it altogether into a cocked hat. And how useful these eggs have proved too. For breakfast, tea or supper they are never out of place. Good nourishing food and appetising withal.

‘The next-door neighbour, too, who complains about the cock crowing, can generally be consoled with a half dozen sent now and again. The shop ones, he knows, offend the olfactory sense, and a too close inspection reveals a distinct portion of an embryo chick. Chanticleer may crow and the hens cackle throughout the livelong day. Their incessant rejoicings, instead of being a nuisance, are listened to with delight: they are, in fact, regarded as harbingers of the approaching gift.’

Laycock described some of that ingenuity by quoting an article in Fowls – a a penny weekly journal exclusively devoted to poultry-keeping.

“The very cheapest [poultry] house we know of is a large, empty ‘sugar-barrel’. This you can obtain at any good-natured grocer’s for a small sum, 1s. 6d we should think at the outside: a price surely within the reach of any working man. Thoroughly cleanse it from all sticky matter, for your own comfort and to save your clothes from damage. Then obtain half a dozen bricks and, having laid them evenly on the ground, set your barrel on its side firmly on top of them.

“This will serve not only to keep it steady but will also prevent the damp from rising through the floor. To prevent the tub from lurching, secure it by a couple of holdfasts to the wall. In one end of the cask cut out a square hole of moderate size for the door, fix it with a couple of small hinges, and attach a clasp and padlock for security.

“Above the door bore five or six holes for ventilation. At the further end of the barrel make a nest out of a couple of bricks placed at right angles to keep in the hay, and be sure you put in a nest egg or two to encourage laying. The house is now complete.

“Now for the perch. This can be manufactured out of a good stout broom handle, sawn off to the right length and well secured. We say, advisedly ‘well secured’ as there is nothing which fowls dislike so much as a shaky roost. Let the floor of the barrel be thickly covered with fine sifted mould or dry ashes, and beaten down smooth; as this will make a splendid floor, and the dry earth and ash prevent smell.

“Roof over the barrel with a piece of stout felt. Don’t buy the cheapest; it is not the cheapest in the end. You can get the very best for about 4 1/2d. per yard. Nail it securely on, and then give it a good coat of tar and sprinkle some fine grave upon it, and you will have a roof that will last for years.”

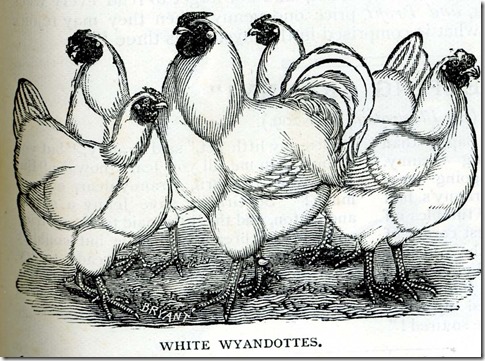

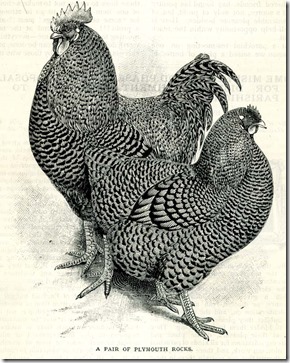

He especially recommended keeping pure breeds as these could be sold at a higher price and were more beautiful and ornamental. He stated later that it was better to keep to one variety rather than ‘a hotch-potch of mongrel blood’.

Several pure breeds were mentioned in articles: Minorcas, Redcaps, Leghorns, Langshans, Andalusians, Black Hamburghs (sic), Buff Orpingtons, Plymouth Rocks (left) and Wyandottes.

Several pure breeds were mentioned in articles: Minorcas, Redcaps, Leghorns, Langshans, Andalusians, Black Hamburghs (sic), Buff Orpingtons, Plymouth Rocks (left) and Wyandottes.

The latter, he said, had a combination of all the virtues: a splendid layer ever in winter and a very good table fowl. But he added: ‘For laying purposes pure and simple there is nothing better than a Minorca. They lay very large white eggs … and lay well all the year round.’ They were, however, only moderate table birds he said. He also accepted that the Langshans were good table birds and excellent layers of dark brown eggs.

In 1895 he was full of admiration for Brown Leghorns. He said the first Leghorns – white ones – had been introduced to England from Italy in 1872. He loved the colours of the Brown Leghorns and wrote that they had hardy constitutions, were excellent egg-layers and reasonably good as table-birds. He added: ‘They seems to thrive here, there and everywhere; on the farm, the country run, or the backyard of the workman’s cottage they will render a good account of themselves. ‘

That year he noted that the main aim was egg production and for that a cock was not necessary. He added: ‘This omission will save annoyance to the neighbours, over-the-garden-wall conversations, complaints to the newspapers on the cock-crowing nuisance, solicitor’s letters, and a sundry visit or two to the police court.’

By then he was also full of admiration for Brown Leghorns. He said the first Leghorns to be imported from Italy in 1872 were white. The brown ones came later and he believed the darker colours were better for small town yards.

Women and girls were, of course, also involved in taking care of chickens and in 1898 there was an article by a Mrs R Browne. She left backyards to men and instead focussed on those living in the suburbs or had a small house in the country. She also believed that a profit could be made from poultry-keeping and wrote: ‘ The keep of a hen throughout the year is on average three halfpence a week. You should make by your eggs about three or four shillings a week.’

She wrote: ‘Cochins, Dorkings, Hamburghs and Minorca fowls are all good breeds but, for a beginner, I recommend Brahma hens crossed with a Dorking cock. This breed are fast growers, surpassing in size any other breed and producing splendid table poultry. They are also hardy, good winter layers, exemplary mothers; and they seldom get out of condition . Brahma hens, if regularly and rightly fed, and warmly housed, will often lay nearly every day in the winter and, if pure bred, are known to lay 30 or 40 eggs before they want to sit.’

She advised that it was best to keep only young birds, and also described how to feed and house them. Her henhouse, however, was far more mundane. ‘A henhouse with five or six hens and a cock to start with, need not to be more than five yards square, with a slanting roof six or eight feet. It must be well ventilated, with nests on the ground and rough bark poles for perches. You must see that the boards are well tongued together and tarred, to keep out wind and rain.’

She told her readers: ‘Poultry keeping can be made a profitable and pleasant occupation for a lady provided she looks after them herself; insists on the strictest cleanliness, regularity in feeding… and does not leave them to the tender mercies of a house-boy or an over-worked maid-of-all-work.’

The illustration (below) for her article showed a girl dressed more for going out to tea than feeding hens!

Very definitely a different audience to Laycock’s working men!