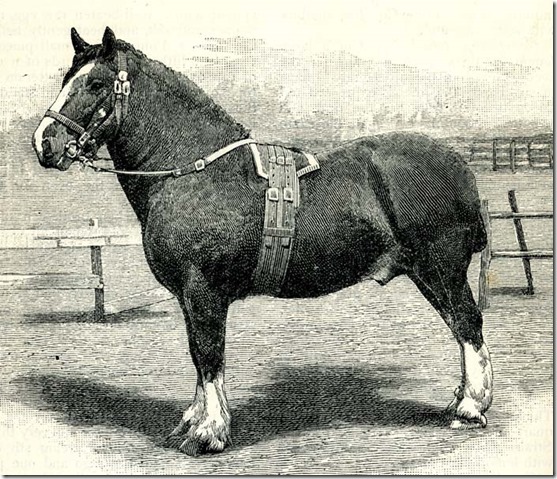

In 1894 the editor of The Church Monthly asked the Rev Theodore Wood FES to write about the horses (like the Suffolk Punch) which were a major feature of life at that time, pointing out the duty of treating them with thoughtfulness and consideration and how they repaid kindness. Wood included a fascinating story about the horses which then worked at Hitchin railway station.

Wood wrote: I will base what I have to say upon two old Arabian sayings.

The first of these refers to the horse in relation to man: ‘God made horses for man and shaped their bodies in accordance with his needs.’

I suppose that most of us have been struck with the marvellous suitability of the horse’s frame to the work which it called upon the perform. We want to ride the animal; and its back seems shaped purposely to receive the saddle. We require to direct its course; and its mouth seems specially formed to receive the bit. We expect it to draw heavy weights, often over rough ground; and we find that its strength is largely concentrated into its fore-quarters. We call upon it to gallop at speed and sometimes to leap over obstacles; and we discover that its feet are provided with strong stout hoofs which not only protect them from injury against the ground, but also serve to break the shock of its fall. For the hoofs are not mere sold blocks of horn but are made up of a vast number of springs which are very similar to those which we use in the framework of our carriages and fulfil exactly the same function. One can scarcely help feeling that the Arabs are right, and that the connections between horse and man did indeed enter into the scheme of the Creator.

But – perhaps by reason of these same natural advantages – we are rather apt to look upon the horse as a kind of live machine. We fail to credit it, for example, with the intelligence which it really possesses. We ‘break’ it to its work, often by a system of perfectly needless cruelty. When it is ‘broken’ we expect nothing more from it than a mere mechanical obedience to our commands. Yet the horse which is allowed and encouraged to work intelligently is by far the better servant; and, when it has thoroughly learned its duties, no animal is more trustworthy.

Take, for example, the huge cart horses which may be seen working any day at Hitchin railway station. The two last carriages of the early morning trains are ‘through coaches’ and have to be backed on to a siding in order that they may be attached to the London express which stops at the station shortly afterwards. This work is performed by horses.

As soon as the carriages are uncoupled the animals drag them away to the siding and there stand patiently for the express. The odd thing is, that they are perfectly aware that the main line expresses, which run through the station, have nothing to do with them and pay no attention to them whatever. But the very moment that the fast train from the Cambridge branch passes they bend to their work, drag the carriages along until they are only half a dozen yards away from the rear of the train as it stands waiting at the platform, and then suddenly step sideways off the line, so that the impetus of the coaches may carry them to just the required spot.

A porter accompanies the animals but he never touches them with whip or rein. He seldom even speaks to them save to utter a word or two of encouragement. And the secret of it all is simply this – that the horses know their work and are trusted to perform it intelligently, as almost all horses will if they are treated kindly and the opportunity is afforded them.

It is scarcely too much, indeed, to say that there seems to be in the horse a natural willingness – almost a natural desire – to recognise man as its master and to serve him to the best of its ability.

The second of the two Arabian sayings refers not to the horse in relation to man, but to man in relation to the horse. ‘As many grains of barley as are contained in the food we give to a horse, so many blessings do we daily gain.’

There cannot be a doubt, on the whole, that animals are better treated than they were. We are gradually awakening to a sense of our responsibilities, although the cruelties which are still too often practised are sickening enough. Horses especially suffer from thoughtlessness and unintentional cruelty.

What else than cruelty is it to strap up their heads with tight bearing-reins and then expect the same amount of work from them as if their heads were free? A horse cannot put out its full strength unless it can lower its head; and to prevent it from doing so is simply to reduce its usefulness by at least one half, and at the same time condemn it to severe and unnecessary torture.

What else than cruelty is it to keep a horse in a stable in which it can obtain neither light nor fresh air? I have been greatly struck by noticing how often, in some of the Hertfordshire towns and villages, the horses of tradesmen and others are kept in ‘barns’ scarcely large enough to contain them, in perfect darkness and with no provision whatever for ventilation. I sincerely wish that a law could be passed to prevent such shameful ill-treatment of an animal which is often the true ‘bread-winner’ of the family. Thoughtless cruelty it is perhaps; but it is cruelty all the same.

Truly there are many ways in which the lot of animals may yet be improved, and a little more thought and a little more consideration will brighten the life of many a hard-working servant of man.

Reproduced with permission of Aysgarth PCC