‘A Ride on a Railway Engine’, by F M Holmes, published in The Church Monthly 1894

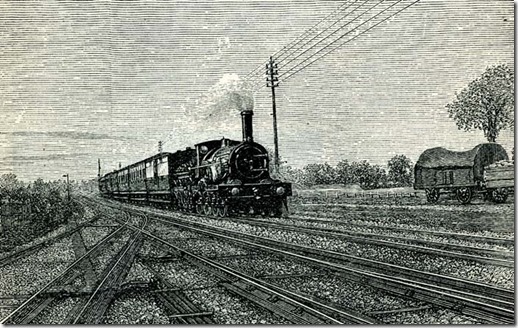

Above: ‘Flying Dutchman’ passing through Collumpton in the 1890s

‘Right away, Jem! There’s the whistle!’

Jem opens the throttle – that is, he turns on the steam – and the engine slowly to move.

Watch him, and you will see that he is lifting the handle of the ‘throttle’ gradually. If he turned on the full head of steam at once the probability is that, with the heavy weight of the train behind, the driving-wheels of the engine would fly round uselessly, and would not grip the rails at all.

Sometimes this does occur when the rails are greasy. Then the ever-ready hand of the driver closes the throttle for the moment and his equally ready fireman sends sand on to the rail through a pipe provided for the purpose.

But nothing happens like this today. And the engine gathering speed – as the steam is gradually increased and the heavy train acquires momentum – is soon flying along through the suburbs of the great city. Then, with a burst, we are into the open country.

The air rushes past so furiously that it seems like enough – as people say – to cut your ears off; and there is a jerking, shaking motion that seems as though it might throw you off your feet. You clutch at a steel rail near by convulsively to steady yourself.

How warm you are on one side as you stand here on the footplate of the engine and perforce near the hot furnace; and how chilly by comparison you are on the other; and how difficult amid this noise and racket to hear what your companions are saying.

‘Signals up!’ A wild shriek startles your ears as the engine whistle rises above the rush and roar of the train, but still the signal does not move. Then off goes the steam. The driver, standing with is hand on the throttle and his face to the window in front, sees there is no alternative, and turns the handle; and his fireman applies the brake.

There is a crippled motion of the wheels and the tremendous speed begins sensibly to slacken. Then suddenly down falls the signal and the line is clear. The watchful driver opens the throttle again, the brake is off, and once more we fly on along the railway at fifty or sixty miles an hour, the passengers behind scarce noticing, perhaps, that a check has been made. A signal against an express is very unusual; and that signalman will probably have to make an explanatory report to the authorities tomorrow as to the reason why his signal was at ‘Danger’.

Then the fireman plies his shovel again. He is always doing it. The quantity of coal consumed by a railway engine would astonish the ordinary householder considerably. Perhaps the majority of people do not know that the waste steam, after doing its work, rushes up the chimney and thus creates an enormous draught, burning the fuel fast and raising the steam quickly. Yet this arrangement is, so to speak, the very life-blood of the locomotive, and is one of the most important principles utilised by Stephenson. The faster the engine tears along the more steam she raises – provided she have a sufficiency of coal and water. There is no need for a forced draught, as in some steamships.

Then the fireman plies his shovel again. He is always doing it. The quantity of coal consumed by a railway engine would astonish the ordinary householder considerably. Perhaps the majority of people do not know that the waste steam, after doing its work, rushes up the chimney and thus creates an enormous draught, burning the fuel fast and raising the steam quickly. Yet this arrangement is, so to speak, the very life-blood of the locomotive, and is one of the most important principles utilised by Stephenson. The faster the engine tears along the more steam she raises – provided she have a sufficiency of coal and water. There is no need for a forced draught, as in some steamships.

The furnace filled up, the fireman seizes a moment for a drink of cold team. Then down comes smart shower of rain, and in a trice the thick pilot coats of the driver and his stoker are out and over their shoulders. But it does not last long; we soon drive through it and the sun is shining brightly again on the long lines of flashing metals that ever and ever stretch ahead.

You gain quite a different view when riding on an engine from when riding comfortably in a carriage. In the latter case you cannot look ahead. You gain views, more or less satisfactory, of the country beside you. But on an engine, through the windows of the ‘cab’ – as the screen and protection for the men is called on a locomotive – your eyes are drawn as by a spell to look forward. There is constantly before you the dry pathway cut by lines of gleaming steel and occasionally broken by a station. And indeed this is one of the most important parts of the driver’s duty, in order to watch the signals. With hand on the throttle handle and face to the window, he guides the flying engine over its iron road.

Then the gauges have to be watched – the steam gauge, which shows how much, or how little, is in the boiler. There seem to be handles all round you. This is the large lever which works the reversing gear of the engine and causes it to travel backwards. This handle admits water to the boiler; and this one blows off steam when the pressure is too great. Another works the brake; and a powerful vacuum or Westinghouse brake [air brake named after George Westinghouse who invented it in New York State in 1869] can be applied all along the train from the engine itself.

The power of these brakes is enormous. Fast expresses can be drawn up in splendid time by their commanding means. At the end of a large station platform the train seems flying along at its normal speed. But almost within its own length it is brought to a stand.

This great brake power is sometimes not without a comical side – to an observer. On one occasion, an engine driver was endeavouring to take out a long line of empty coaches from a certain metropolitan station. For some reason, which he could not understand, his engine would scarcely move. The steam was all right, his brakes were all right, yet the big train to which he was attached only crept along. At last he jumped from his engine and hurried to the guard’s van. With a roar he proclaimed the secret – the brake was ‘on’ there crippling all his efforts! In a moment, however, it was ‘off’ and he was soon down the line with his empty carriages.

The keen watchfulness of signals is one of the most important duties of enginemen. They pass hundreds in the course of the day and, according to the state of the signal, so have the men to act, or refrain from acting. That signal-arm we can see far along the line… that arm, growing larger as we quickly approach it, lowers to allow us to pass. We fly by at lightning speed and, in a second, it rises again to prohibit anything else from following us till we are far ahead and beyond the next block-space of line.

How fast can a train travel? It is not an easy question to answer. Probably the average rate of most English fast trains is about 45 miles an hour. But it must be remembered that in order to attain this average speed, including all stoppages and ‘pantings’ up heavy gradients, the train must sometimes run much faster. A mile a minute is often accomplished. Mr W. M. Acworth tells us that a Worsdell ‘compound’ engine once ran from Grant’s House to Berwick at 76 miles an hour for some miles in succession as indicated by the speed register on the engine. And the 2 p.m. Great Northern from Manchester, one of the fastest regular trains in the world, was reported in the Engineer to have rushed over short distances at the rate of 78 miles and 76 miles per hour from Grantham to London.

It is competition, no doubt, that has something to do with this quick running. By the Great Northern route Manchester is 203 miles from London, by the North Western 189 miles, and by the Midland 191 1/4 miles. In order, therefore, to compete successfully with the fast 4 1/4-hour expresses of the North Western, the Great Northern must run faster by about three miles an hour.

The kind of road over which the engine travels has a good deal to do with its speed. Up hill and down dale spoils the pace of engines as of horses; and a moderate average speed – on paper – over a hard road may be really better work than a sensationally high record along a flat valley. Then there is economical stoking to be considered. The drivers engaged on certain classes of work are, on one line at least, formed into a party or, as it is called, a ‘link’. All the coal and oil supplies to each engine is put down and the amount added up weekly and divided by the number of miles the engine has run. A notice showing how much each man has used is then exhibited, the most economical, combined with punctuality, being of course placed at top. The good stoker should, at the end of the engine’s work for the day or night show a clear fire burnt to the bars, but with undiminished steam pressure.

Enginemen know their engines like their alphabet and their roads like their native town. As each locomotive contains something like 5,000 separate pieces, this knowledge is not acquired in a day. Drivers have long and arduous preparation to plod through before they are promoted to the foot-plate of an express, and they have onerous work when they get there. But it is worthy of a man – a man with a good head on his shoulders and steady courage in his heart.

[Today we can say man or woman…]

reproduced with the permission of Aysgarth PCC.