‘A Night in a Herring Boat’ by the Rev A M Fosbrooke, then curate of Stoke-on-Trent

It was three o’clock in the afternoon when we started from Port Erin. There were eight of us on board, seven fishermen and myself. The dingy having been hauled up, and the sails hoisted, in a few moments the strong breeze blowing carried the Puffin out of the bay and westwards towards the Irish coast.

We had a mackerel-line out and, though the boat was going much too fast for satisfactory fishing, about half a dozen were caught before evening. The sky became dark and cloudy and, before long, the rain descended in torrents, so as to make one thankful for the oilskins, sea boots, and sou’-wester which a sailor had kindly lent. About 8pm the sky cleared and we were favoured with a beautiful sunset. The wind fell and practically no further progress could be made, so it was decided to ‘shoot’ the nets.

We were about mid-channel – the Manx coast on the one hand and the Mourne Mountains on the other being distinctly visible. A large number of puffins and other birds were flying about which made the men think they might have a successful night. The sails were lowered with the exception of a small jib; and as the boat slowly moved on by means of this one sail the net was cast out, it being connected at intervals to a strong rope called the ‘spring-back’, the same length as the net, the purpose of which will be explained in a moment. The two are connected together by one of the men as they are thrown out.

Let me try and explain the nature and position of the net as it lies in the water. On the surface there are large cock floats about every ten yards; from these hang down thin ropes, called the ‘straps’, about nine feet long, which are fastened to the spring-back. From this, again, hang thin ropes called the ‘legs’, about 12 feet long. These are fastened to the rope along the top of the net which is called the ‘back’, and the net itself, weighted at the bottom to keep it perpendicular, is about 30 feet deep; so that from the surface of the water to the top of the net is about 21 feet, to the bottom of the net 51 feet. The length of the net is about one mile or sometimes longer than that.

The object of having the net so far below the surface is partly, of course, as being more favourable for catching the fish, but also to enable any ship which might happen to cross the net to do so without causing any damage. Even still, a ship drawing a great deal of water such as our ironclads, will sometimes carry away their nets to the great loss of the fishermen.

The whole of the net having been ‘shot’ out, the large mast is lowered in order that the boat may not roll so much in a rough sea and also to prevent the wind catching her so much. A small sail at the stern keeps her steady with her head to the wind. A light is put up as a danger signal, one man stays on deck to keep watch, the rest retired for the night. And there the boat lies tossing aobut on the rolling waves, looking very much like a wreck, with her mast lying down and her ropes hanging loosely about.

Before we lay down to rest in the small cabin … an evening hymn was sung and prayer offered by one of the men, commending themselves and their loved ones to the care of our Heavenly Father and asking Him to ‘preserve to them the produce of the seas.’ This is an old time-honoured custom among the fishermen; it is still kept up on many of the boats, though not on all. It was rather a remarkable fact that all my seven companions that night were total abstainers. Nothing of an intoxicating nature is allowed on board the Puffin.

It was very hot and stuffy with seven of us in the small cabin, about three yards long by two yards wide, and a hot fire in the grate on an August evening! This heat and the rolling of the boat in a rough sea were very conducive to sea-sickness. I was not sorry when at 3am the day began to dawn and all hands were called on deck to haul in the net. This, of course, is the most interesting part of the proceedings.

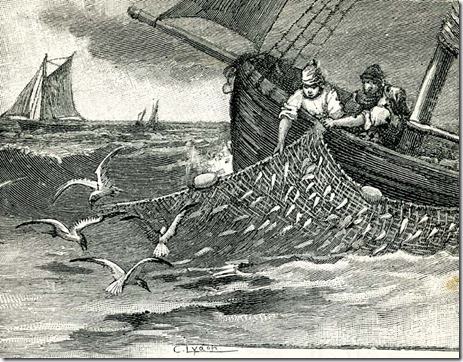

The net is no drawn in from the two ends, enclosing the fish, as many of us might suppose, but just hauled in from the one end in the following manner: Two men work at the winch, hauling in the spring-back. The boat is thus gradually drawn along by the weight of the net. Another man unfastens the cords connecting the spring-back to the net; two others haul in the net and set free the fish; one arranges the net in order in the hold as it comes in, another coils up the spring-back in another part of the hold; so that the seven men are really required for the work. The fish are caught by swimming into the net and getting fastened by their gills in its meshes. Then, as the net is hauled over the bulwarks, they are pulled off one by on or, if the catch is a large one, they are shaken off on to the deck by jerking the net.

Unfortunately, the fish seem to be leaving the Irish Sea; for the last four or five years only very few have been caught. Only 400 were taken on this occasion and many a night they do not take so many as that, whereas in the good days they could take as many as the boats could carry. They have sometimes been known to take as many as 100 ‘mease’ (a mease = five full hundreds of 120 each). One cannot help feeling great sympathy for the fishermen in the poverty and distress which seem to threaten them at present. The hauling of the net took over an hour. Then the mast of the boat was re-erected, the sails hoisted, and her bow turned towards home.We caught a few more mackerel with the trawling-line while returning.

Breakfast was prepared on board consisting of coffee, bread and butter, and a real fresh herring, which was most delicious. The sun rising over the Manx hills and lighting up the sky with very varied tints made a beautiful picture. A strong, favourable wind bore us on at a great speed and by 8am I was back again in Port Erin Bay after a very interesting and enjoyable experience.

transcribed from The Church Monthly annual 1894 with permission of Aysgarth Parochial Church Council.