From ‘Up in a Lighthouse’ by F M Holmes, published in The Church Monthly annual 1894

Above: The Inchcape Rock Lighthouse

‘Take care! Mind how you go! These steps were not built for unaccustomed visitors.’

‘All right, I can manage, I am used to strange places.’ And clinging tightly to the rail we mount the almost perpendicular stairs.

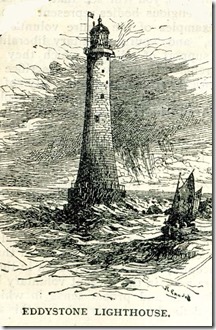

So solid is the masonry around, so firmly jointed together and so smooth for the raging sea to slip past without doing any damage, that the broad-based tower seems as thought it might live for ever.

Look below at the foundations. ‘Aye, they are cut deep into the solid rock,’ says the lighthouse keeper; ‘and then for 20 or 30 feet up the tower is built strong blocks of granite dovetailed together.’

At about that height the dwelling rooms commence, one above another, and are reached by ladders. Three men always live here, the full staff being four; but one is usually away on shore, the men going off duty in rotation.

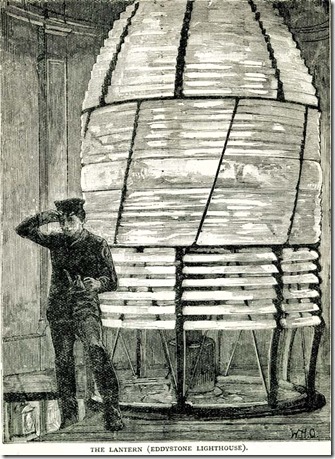

At the top of the tower rises the lantern – of strictly speaking, the lamp-room – about 10 feet high, whence the guiding light flashes forth over miles of sea.

At the top of the tower rises the lantern – of strictly speaking, the lamp-room – about 10 feet high, whence the guiding light flashes forth over miles of sea.

The lantern is largely made of glass, like a hothouse; and splendid views you can gain through its glazed sides of miles of heaving seas. A blue expanse it appears this afternoon, flecked with white in the summer sunshine.

In the room itself glass and bright metal glint everywhere. It is domed with copper, and fitted with quarter-inch or half-inch plate glass ‘sides supported in diagonal astragals, or mouldings of gun-metal. These are so arranged that they do not intercept the light when it is required to beam forth.

In the centre rises the lighting apparatus and, at first sight, it seems something like a mound of prisms. What can be the reason for all these ribs of glass? The answer is that they help to condense the rays of light into one strong beam.

‘Why, I suppose our light here,’ says the lighthouse keeper, ‘can be seen for nearly 20 miles – 17 at least, and perhaps more.’

‘But I can’t see how these curious triangular ribs can accomplish that.’

‘Well, you must know – nearly everybody knows – how much a shining reflector behind a lamp intensifies its light in one direction. And the mirror is usually concave to bend the rays that radiate above and below more decidedly into one line. That is what these reflectors accomplish; only far, far more effectually. A parabolic reflector 20 inches or so across will increase the light-giving power of the lamp about 400 times, or even more.’

‘Then these prisms are to bend down the rays of light that would rise too high, and to bend up the rays of light that would sink too low?’

‘Exactly; we do not want to try and illuminate the sky and the sea; we want to send strong beams as far as we can round the horizon. A lighthouse is a guide, rather than an illuminator, like a street lamp.’

‘And why have you several reflectors group round like this?’

‘In order to send several beams of equal power all round the horizon, where these is sea. That arrangement gives what we call a fixed light. For a revolving light, if the reflectors be grouped on a frame, with only two or more faces as required, and the frame be caused to revolve, light and dark intervals are, of course, produced – for the light only shines through the faces. In a similar manner, by a suitable arrangement of the reflectors, a group-flashing light is produced – that is, a light giving two or three flashes and then a brief period of darkness. Light of different colours can also be shown.’

‘Ah, just so. It is by such means as these that lights are given their characteristic and distinguishing features.’

‘And, by nothing their number of flashes or other peculiarities, a sailor can tell what light it is and consequently determine, more or less, his position. Of course, we have a lens as well – even a policeman’s bull’s-eye lantern has a lens – and with the numerous wicks and large lamp-flame now used, and the big prisms bending above and below, there is not a ray of light that escapes.’

This system is called holophotal. The word means reflecting or refracting light without loss of light. Paraffin is the illuminant. ‘Nearly every sort of oil haws been used,’ says the lighthouse keeper, ‘but paraffin comes to the top. It burns brighter, and it is cheaper.’

Peering into the midst of the prisms to see the gigantic lamp itself, we distinguish not one wick but many – seven in fact, like concentric rings – one within the other. Some lights, indeed, have nine wicks; this multiplication of them, of course, greatly increasing the illuminating power. With these numerous wicks, the oil has to be supplied by clock-work pumps, or pushed by a heavy piston. An overflow pipe permits the paraffin to run back to the fountain should it at any time rise above a certain point.

The electric light has also been used with great success at various lighthouses; and for harbour lights, where gas may be readily obtained, that illuminant is sometimes employed. But at times even the most powerful illuminants are obscured by fog – what then?

Then this curious-looking trumpet comes into play. Terrible is the nose it makes. No human breath blows it. Gas engines are needed, and in some lighthouses oil engines and compressed air are used to evoke its ear-splitting but useful sound. When the day is dense with obscuring fog and even the light of a nine-wick lamp, focussed into a few powerful beams by many prisms, can struggle but a poor mile or two into the bewildering gloom, then this trumpet, called by strange irony a siren, will shriek forth its warning blasts.

There are two discs in the siren-trumpet, each disc a foot in diameter, and with a dozen radial slits. One disc is fixed but the other rotates rapidly, nearly 2000 times a minute. Sirens can be so arranged as to give signals, such as two or three blasts in rapid succession at certain intervals; and the passing sailors should then know the lighthouse, even as if they could see its characteristic light. The shriek of the siren can be heard sometimes for ten miles. Charges of detonating powder are also fired at some stations, electricity being used to explode the cartridges; so that when the light fails to piece the shrouding fog, the lighthouses still strive to perform their duty of guiding and warning, by means of thunderous sound. A little-known explosive called tonite is sometimes used for these warnings. Tonite appears to be a mixture of gun-cotton and nitrate of baryta forced into a cartridge like a candle.

‘And what are those panes?’ you ask; looking a frameworks of copper filled with glass.

‘And what are those panes?’ you ask; looking a frameworks of copper filled with glass.

‘Storm panes,’ is the answer; ‘they are kept in readiness should a pane of glass be broken in the lantern.’

‘And do you often have to use them?’

‘Very rarely; and then it is generally because birds or stones are blown against the lantern glass in a tremendous gale. It is very seldom that the wind alone breaks the glass. You see these gun-metal mouldings and thick plate glass panes are very strong.’

‘Do birds break the glass?’ exclaims some one in surprise.

‘They do so, and no mistake. You might be watching here some dark night and see scores of birds beating against the glass, and blown hard against it. Perhaps they are migrating to another country at the change of seasons, or perhaps they are coming to this land. Anyhow, there they are; likely enough they are tired out with their flight and attracted by the light, or knocked against the glass by the wind.’

What a different scene is thus conjured up, from the calm, bright summer sunshine of the lovely afternoon. But whatever the moods of weather – though tempests rage and torrents of rain lash the streaming glass; though the storm-tossed billows strike the house with thunderous sound, and dash the spray high up the sides; though the blasts seems to shake the massive tower with the fury of wind and wave; though choking fog encompass it around, or the calm moon rides in a cloudless sky – yet still in every change of changeful life this friendly beacon sends forth its warnings of light and sound.

Reproduced with permission of Aysgarth Parochial Church Council