From The Church Monthly in 1894: “Out with the Fire Brigade” by F M Holmes

The startling clang rings through the room and a tablet has fallen on the wall, not far from your head, revealing the name of the London street whence the alarm was given.

Some one has broken the glass and pulled the handle of the fire-alarm post in that thoroughfare, and instantly all the arrangements of the station for proceeding to the fire are set in motion.

There are always men on duty, and more alarm bells ring with noise enough to wake the proverbial Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. A pair of horses are always in readiness, their noble heads, full of animation and expectancy, turned towards the stable door and the light harness hanging over them, ready to descend at a second’s notice, is dropped on their backs.

The intelligent creatures know the ring of the alarm bell as well as the men and are as eager to be off. The preparations are so complete that, when a rope is pulled, down falls the harness. Full of excitement, the steeds are led to the engine which, in its turn, is as fully prepared as are the horses. The traces are hooked on, the men jump to their seats, and with the startling cry of ‘Fire! Fire!’ screamed as only a London fireman can utter it, the engine tears out of the station and into the street. Less than two minutes has elapsed since the ringing of the alarm bell; and the engine is already on its way.

Most exciting is the rush through the streets. Quick movement through the air is usually exhilarating at any time and to this is added the excitement of the fire and the startling cries of the firemen. Everything scatters before us. Even the red carts of the Post Office – which may trespass on the thoroughfares reserved for royal processions – have to give place to the dashing Fire Brigade.

With steam hissing from the boiler, with horses all aglow with excitement, and with alarming cries of ‘Fire! Fire!’ ringing along the street, a pathway opens as if by magic through the most crowded thoroughfares; and almost before you know it you have arrived at the scene of the fire.

Here the excitement is no less; but the men are as cool as cucumbers. ‘Play on that part of the building’, comes the order, hardly sooner said than done. The engine, which a few minutes ago was quiet at the station, is now at vigorous work some miles distant from its home.

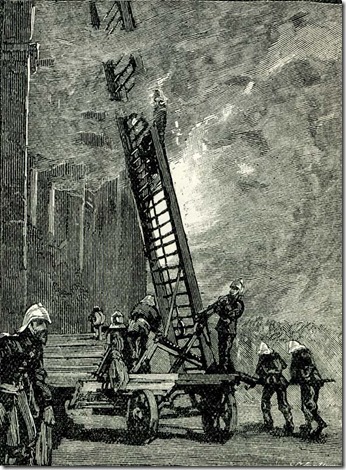

The flames burst out through the veil of smoke and leap upward to the sky. The gathering crowd press forward with excited faces and are, with difficulty, kept back by the few policemen on the spot. A cry raises: ‘Somebody is in the building!’ And here comes the fire-escape which will reach the highest windows. It is placed against the house and quickly a fireman mounts. See! he has rescued a mother and child, and he brings them down amid excited cheers. Sometimes he has a much harder task; for he enters the burning building and gropes amid the blinding smoke and scorching heat to rescue the half-suffocated sufferers from the flames.

The flames burst out through the veil of smoke and leap upward to the sky. The gathering crowd press forward with excited faces and are, with difficulty, kept back by the few policemen on the spot. A cry raises: ‘Somebody is in the building!’ And here comes the fire-escape which will reach the highest windows. It is placed against the house and quickly a fireman mounts. See! he has rescued a mother and child, and he brings them down amid excited cheers. Sometimes he has a much harder task; for he enters the burning building and gropes amid the blinding smoke and scorching heat to rescue the half-suffocated sufferers from the flames.

Meantime, other engines have arrived. Each fulfils its part. While some are playing on the fire itself, others are drenching surrounding walls with water to prevent the fire from spreading; and ere long the officer in charge will be able to report that the fire is localised and mastered. Wise forethought, as well as smart promptitude on the part of the men, have contributed to these satisfactory results.

If you had inspected the engine you would have found everything ready for instant departure – the fire laid, axes, hose, and apparatus in position; but you would also have found two things which perhaps you would not expect. Under the boiler is placed a movable gas jet which keeps the water always hot; and by the funnel is large fusee [a large-headed match capable of staying alight in strong winds].

When the alarm sounds, one of the men on duty ignites the fusee at once – he knows exactly where to find it – and drops it down the chimney. The fusee is certain to flame well and lights the material below, already prepared to receive its fiery touch. The quick rush of the engine through the air does the rest; for the speed creates such a strong draught that the engine fire soon roars in its box, and raises the heated water to steam.

The steam in the fire-engine is used for pumping the water and throwing it on the burning building. But, successful as it is, the steam fire-engine has not superseded the use of manuals; while for small fires – of which there are a great number in the Metropolis – the little portable hand-pumps are said to be of the greatest value. These little pumps can be used anywhere, and taken into rooms where the fire may be burning. Speedily used they will, in ordinary circumstances, quickly extinguish the flames and prevent a little conflagration from becoming a big one. The water for their use is contained in a bucket which is supplied by other buckets of water handed up by assistants.

Valuable as these little pumps are for small fires, however, there is need, of course, for the glittering and powerful steam fire-engines for bigger fires; and of these ‘steamers’ the Brigade have fifty on land and about ten floating on the Thames. There are also a large number of manuals. Their wheels are broad and tired with wavy iron bands which project in some places beyond the sides of the wheels themselves.

Many persons, no doubt, would puzzle for hours over the reason for these strange iron tires; but the reason is simple. They are used to prevent the wheels from canting or tripping at the tram rails which seam so many London thoroughfares. It would be a bad accident, and a terrible hindrance at a critical time, for a fire-engine to be overturned when driven at a headlong pace to a fire. In the same way, should a horse fall when tearing along, the harness is so arranged that the turning of a swivel-bar at the end of the engine-pole dividing the two horses, will free the animal in front, and he can be unhooked and helped to his feet again in a trice.

The hose also is subjected to a most severe testing before being used. At a fire, the water is forced through the hose at a pressure of a 110 pounds to the square inch. For a hose to burst under this strain would be a great disaster. Consequently, every length is tested up to the severe strain of 300 pounds to the square inch, so that it is as certain as anything mortal can be to stand firm in actual work. The hose is now made of strong, India rubber-lined canvas which is light and flexible as well as tough and tenacious, and has quite superseded the old hose, made of pieces of leather and riveted together by metal fastenings. The hose for the suction-pipe, communicating with the water supply, is usually stiffened by spiral wire and is still very flexible.

A fire-engine, therefore, has to do two things: it has to draw large quantities of water from a suitable source of supply; and it has to throw that water, steadily and continuously, and sometimes to a great height, on to the fire. This is accomplished by means of force-pumps in the engine and an air-chamber. The pumps draw water through the suction tube from the water pipes under the street, or other suitable source of supply, and force the precious fluid into a strong air-chamber or chest, thereby compressing the air in that chest to a high degree. But, having pressed the air to a certain point, the air itself will, in its turn, become stronger than the fore-pumps, and exert pressure on the water, which it forces out through the host to the fire. It will continue to do this until the water sinks in the chest. So long, therefore, as the two pumps force water into the chest, up to or above the requisite level, so long will the compressed air expel the water to the fire in a steady and continuous stream. The two pumps are arranged to work reciprocally – that is, one is drawing water, while the other is forcing it into the air-chamber, each in its turn.

The rule is that a steamer shall go from one station and a manual from another station in the neighbourhood. Thus, the stations are not left without resources should another fire break out in the district. All the Metropolitan stations are connected by telegraphic or telephonic communications, so that the Headquarters at Southwark can be acquainted with all that occurs as regards fires in the Metropolis, and a large force concentrated speedily, if necessary, at any point. In addition to Headquarters there are five District Stations, each having a superintendent in control of the district, and having telephonic speech with Headquarters, and with each station in the district.

Being liable to be rung up in their sleep, firemen are, so to speak, kept constantly on duty, except for 24 hours in every 14 days which is their ‘day off’. Should, unfortunately, several fires occur about the same time in the same neighbourhood, the men may have to work for some 36 hours at a time. And, on returning from a fire, the hose has to be cleaned and scrubbed, and hung up in the hose-well to dry; the engines have to be kept in good order, and prepared for another journey at once should necessity arise.

Constant vigilance is the order of the day with the Fire Brigade; and to this is added elaborate preparation and daring bravery. Most of the outside public see only the headlong speed and feel the exciting thrill of the fateful moment; but behind and around that dashing ride lies the most careful fore-thought.

Reproduced with the permission of Aysgarth PCC.

Steam fire engines were in use from the 1840s until the 1920s. For more about them and a photo of horses pulling one at speed click here