For me the Remembrance Service at St Andrew’s Church, Aysgarth, was particularly poignant for several reasons. First, as the names of The Fallen were read each soldier was so real to me after having spent weeks preparing the display for the Festival of Remembrance exhibition. Secondly, my final duty after 14 years as a Community First Responder was to ensure that a wreath from the Yorkshire Ambulance Service was included among those laid below the memorial plaque.

Thirdly, there was the memorable address by Juliet Barker in which she reminded us that World War One was a time when ordinary people did extra-ordinary things. (See below)

About 180 residents attended the Short Acts of Remembrance at village memorials at Aysgarth, Carperby, Thoralby and Thornton Rust that Sunday morning. Many then joined the procession to the church for the Remembrance Service passing the wooden ‘Tommies’ along the drive from the WW1 memorial gates on Church Bank (above). The memorial pillars had been renovated ready for the festival.

The church was full for the service which was led by the Rev Lynn Purvis-Lee and Reader Ian Ferguson. Wreaths were laid by the Deputy Lord Lieutenant of North Yorkshire Brigadier David Madden on behalf of the Lord Lieutenant, and Lieutenant Colonel Peter Wade (British Legion), Cllr John Dinsdale (Aysgarth and District Parish Council) and Neil Piper (Aysgarth church).

Juliet’s address:

Exactly one hundred years ago today, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the guns on the Western Front fell silent as the Armistice that was to end the First World War came into force.

While the crowds back home in England went wild with joy, cheering, singing and getting drunk, the men actually serving in the trenches at the time spoke only of a sense of anti-climax. ‘We were drained of all emotion’, one said. ‘You were so dazed you just didn’t realise that you could stand up straight – and not be shot’, said another. Sgt-Major Richard Tobin summed it up:

‘The Armistice came, the day we had dreamed of. The guns stopped, the fighting stopped. Four years of noise and bangs ended in silence. The killings had stopped.

‘We were stunned. I had been out since 1914. I should have been happy. I was sad. I thought of the slaughter, the hardships, the waste and the friends I had lost.’

The scale of the slaughter over those four years is unimaginable, even by our standards today, and the statistics are worth repeating. Across Europe nine million soldiers died. A third of all British men who were aged between 19 and 22 in 1914 were killed.

At small public schools, which provided most of the officers, the proportion was even higher: the headmaster of Loretto, near Edinburgh, (who lost three of his own sons) observed that every boy who had left school fit to serve over the four years of the war had joined the army: over half of them had been killed or wounded.

Even on the very day of the Armistice itself, 863 Commonwealth soldiers were killed – the last one, Private George Price, a Canadian, who was shot by a sniper in Mons, died at just two minutes to 11.

This was a war that affected the whole of our country on an unprecedented scale. Although it was the big industrial towns with their ‘Pals’ regiments who suffered the heaviest losses, it is worth observing that out of all the 13,702 civil parishes in England and Wales only 53 or 54 welcomed back alive every man who had left to serve – the so-called ‘Thankful Villages’.

Statistics like these may give us some idea of the sheer numbers who died but what they cannot do is reveal the devastating human impact of each and every one of those deaths: the bereaved parents, the wives made widows, the orphaned children, the women who would never marry because a third of their generation of young men had been wiped out. Nor do they tell us of the lasting impact on those who survived, but had to live with sometimes horrific physical and mental injuries; or the many hundreds, if not thousands, who died of what was classified as influenza or TB – though in fact it was actually the result of being gassed.

Every Remembrance Sunday we pledge ‘We will remember them’. But even if we honour their sacrifice, how can we actually ‘remember’ people we don’t know? And as the years pass, fewer and fewer of us can claim to have known anyone who lived through, or fought in, the Great War of 1914 to 1918. When their names on the war memorial are read out, how many of us know who these men were? How many of us have wondered, like me, if repeating the name of Pte Matthew Heseltine is simply a mistake?

This centenary year of the signing of the Armistice seemed a particularly appropriate time for us to hold our Festival of Remembrance – an opportunity for us to come together as a community so that we could gather and preserve the stories of the men and women from our parish who served in WWI, before they are lost forever. So when you hear Pte Matthew Heseltine’s name read out twice, you will now know that it is not a mistake, and that these two young men were cousins from farming families in Thoralby and Newbiggin, who not only shared a name, but enlisted into the same regiment on the same day and, aged 21 and 22, were killed in action at the Somme – on the same day, 14th September 1916.

And you’ll also know that Pte John Percival of the Motor Corps, who is buried in a Commonwealth War Grave in our churchyard, was actually 21-year-old Jack, son of the huntsman of the Wensleydale Harriers, who fought all through the Somme in the Yorkshire Regiment alongside the Heseltine cousins, and was only transferred to the Motor Corps after being severely wounded. Sent back to France, he was badly gassed in October 1917, discharged as unfit for further service and brought home by his family to die. Jack has the dubious distinction of being commemorated on more local memorials than any other man from our parish.

For every man on our memorial there is a story: 19-year-old Pte William Edmund Bushby, who won the Croix de Guerre but was killed in action only nine days before the Armistice; 28-year-old Gunner Timothy Spensley Percival who died of his wounds five days after it; 26-year-old Pte George Sydney Gould and 28-year-old Pte James Pickard Bell, who had both emigrated to Canada in search of employment and a better life, as so many young Dalesmen did during the first decade of the 20th century, but returned to fight in defence of king and country, and were killed for their altruism.

But there are also men born in the parish whose names had already slipped from memory when the memorials were erected in the years immediately after the war: Pte Albert Dinsdale Bell, of Thoralby, for instance, who was killed in action on the Western Front in 1917 and Pte Walter Percival, of Thornton Rust, who was only 19 when he died of dysentery as a Prisoner of War in France.

Thanks to the extensive research undertaken by Penny Ellis, our First World War Roll of Honour for The Fallen of our parish has now risen from 20 to 32 men. But what the new Roll of Honour also does is commemorate the service and sacrifice of the men – and women – from this parish – 193 of them – who went to war, but came back again.

One of the popular vaudeville songs about American soldiers returning from France posed the question in its chorus ‘How ‘ya gonna keep ‘em down on the Farm? (After they’ve seen Paree)’. The idea that there was a wider world outside the small farming communities in which they had hitherto spent their lives was one which certainly spoke to some of the women who joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment.

May Heseltine, who served as a nurse in Egypt and lost her brother and cousin in the war, had no intention of returning to Thoralby once it was over, choosing instead to take up a nursing career in America. Madge Blades, who trained with her, would also have liked to remain a professional nurse in Leeds, but succumbed to family pressure to return home, becoming instead the pharmacist at the doctor’s surgery in Aysgarth – and organist at this church for a remarkable 69 years.

By contrast, the men who had lived through the horrors of the trenches and served at the Front, seem to have been quite content to return to the Dales and pick up the threads of their old lives as far as they were able to do so. Many of them had been injured, some of them repeatedly, and some of them endured constant pain; some of them had been gassed and would suffer from breathing problems for the rest of their lives, which were often cut short because of their wartime experiences. We live in an over-sharing age, but these men kept the burden of their terrible memories to themselves: only when they were with other veterans would they feel able to talk freely – and would always fall silent if someone else entered the room.

John Leyland’s friends and neighbours would only learn at his funeral in 1942 that this staunch Quaker and conscientious objector had won the Croix de Guerre for driving ambulances to the front line, under heavy shelling, to collect the wounded.

And despite everything that had happened to them, most of them kept their faith and remained stalwarts of church and chapel. Some of the most poignant exhibits we have on show are examples of this: the tiny Bible, carved with a nail out of a piece of marble from the rubble of Ypres cathedral in 1918 by a local stonemason – whose family are still local stonemasons; the well-thumbed prayer and hymn book (see Pte W T Dinsdale) which accompanied a soldier to the Front and falls open at his favourite hymn:

‘There is a blessèd home

Beyond this land of woe

Where trials never come

Nor tears of sorrow flow…

There is a land of peace

God’s angels know it well ….

Look up you saints of God

Nor fear to tread below

The path your Saviour trod

Of daily toil and woe.

For Ant Fawcett, and the thousands of men like him facing the sheer horror and terror of daily life – and death – on the Front Line; experiencing the worst that human beings can, and do, inflict on each other; there was comfort and hope in trusting and believing in a Saviour – our Saviour – who shared both our humanity and its sufferings. A Saviour who, in that inspirational Gospel reading we heard today, commanded His followers to love one another, as He had loved them.

This goes to the heart of Christian teaching. Love is not only stronger than death, it is the path to life and to salvation. It is selfless and therefore it is sacrificial. ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’ Jesus told His disciples as He prepared to go to His own death so that we, his friends, might have eternal life. His words appear on so many of our war memorials because they reflect the sacrifice made by so many who also gave their lives for those whom they loved.

If our Festival of Remembrance does nothing else, I hope it pays appropriate tribute to the so-called ‘ordinary’ men and women of our dale who, not of their own choosing, were called upon to do extra-ordinary things.

In a period when hatred and violence seemed all-powerful, they demonstrated time and again the selflessness of love: love for their families and friends back home (‘Don’t tell mother so much about it’ one young man drafted into a tank unit nick-named ‘The Suicide Club’ writes home to his brother, ‘I know she will take it badly’). And love for their comrades whose lives they held dearer than their own in the hell on earth that was the battlefields and trenches of the First World War.

By telling some of their stories I hope that we will be able to say, with renewed conviction and greater understanding than before: ‘We will remember them.’

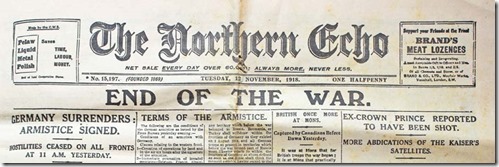

(Photo of front page of the Northern Echo Tuesday, 12 November 1918, courtesy of John Suggitt. A copy of the front page of that newspaper is still on display on the Home Front board in Aysgarth church.)

For photos of the Festival see Aysgarth Festival of Remembrance.

(Sadly I had to resign as a community first responder due to back problems)