“There is a nation to clothe,” wrote a Miss M’Laren in 1840 begging women in Britain to send pinafores and dresses for the girls at her mission school in South Africa. She was the second to be sent by the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East (SPFEE)1 to South Africa and was a true pioneer, travelling by waggon train in December 1839 to an Xhosa area not then annexed by the British or colonised by Boer farmers.

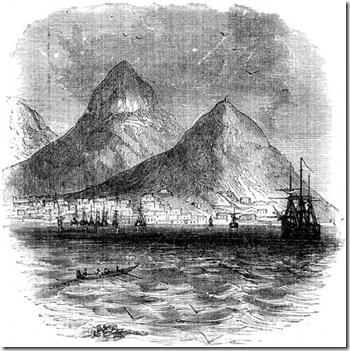

Miss M’Laren left England in August and arrived in Cape Town (pictured above) on October 22, 1839. She may have travelled with Rebecca Irvine Olgivie who married the Rev Robert Niven in Cape Town in November2.

Niven was with the Glasgow Missionary Society and in 1836 had opened a mission station at Igqibigha, near Alice in what is now the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. By December Miss M’Laren was en route with the newly-weds to an area which had not only been ravaged by frontier wars since 17793 but also by tribal battles over land and cattle. On the way they visited Port Elizabeth, Bethelsdorp, Graham’s Town and the Lovedale Mission two miles north of Alice.

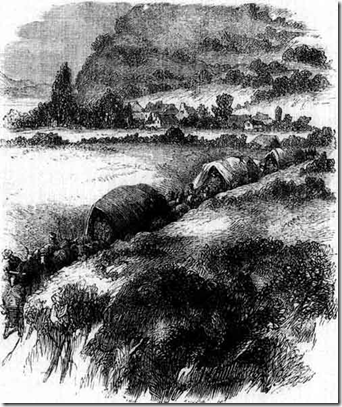

Of their journey Miss M’Laren commented: “Waggon travelling is by no means agreeable, though very convenient, and the only suitable mode for such a country, except horseback, which I was glad to recourse to occasionally, and rode about seventy miles of the way.”

According to two Quaker missionaries, James Backhouse and George Washington Walker, who visited Igqibigha in February 1839 the mission consisted of a temporary chapel in a beehive hut and a stone house with a few simple plain rooms one of which was used as a schoolroom. There were a few Xhosa huts nearby and 15 kraals within six miles which Niven visited regularly. Backhouse stated that not only were the Xhosa accustomed to predatory warfare but often many were killed during cattle raids. Even so 100 to 200 often attended services at Niven’s temporary chapel.4

In January 1840 Miss M’Laren wrote to the SPFEE : “Mrs Niven’s arrival and mine excited a great deal of interest among the natives, who flocked from all quarters to welcome us. It was quite a new thing to have white females among them, and their curiosity was intense, especially among our own sex.

“They were not satisfied with our going out to shake hands with them, but continued buzzing about till evening, peeping in at every window, trying to catch another sight of us.

“Mr Niven invited them to come and get something to eat next day, and then we would say something to them. We met above 300 of them on the grass, many of whom had come several miles, all in their native kaross5, and with abundance of ornaments on fingers, hands, arms, legs, ears, and neck. They have quite a passion for ornaments, and some of them display a good deal of taste in the arrangement of them.

“We told them, through Mr Niven, what we had come to do. They listened with great attention, and showed much interest. The children seemed so anxious to come to school, that I thought it better to begin and do what I could with them.

“I accordingly commenced the Monday after our arrival. The first day I had about thirty, the day after about sixty; but many of those came from a great distance, and are not likely to come often.

“I got them all cleaned and dressed in the pinafores from Ireland, and some of the dresses you sent: and really the change in their appearance was very great.

“After suitable exercises I began with sewing, at which they are making very rapid progress. I cannot yet do more than this, till I know more of the language. I find the children very docile and eager to learn.

“I am anxious to get them all decently dressed to get them to lay aside the kaross entirely, and wear European clothing. Should any kind friends be again inclined to send some clothing for the women and children here, I would suggest that it should be in large, dark, strong pinafores for the girls, some of them pretty long, and gowns for the women.

“I mean to beg from all my friends, for here there is a nation to clothe.”

She found the language difficult to learn and Niven was often away so couldn’t translate for her.

Although the countryside was beautiful she felt isolated at the mission station as it was in what she described as a sort of amphitheatre with hills rising up around it. “I feel the solitude a great deal, and the want of all civilisation is a trial.”

Niven had been surprised at the interest shown by so many girls. Even so by April the number attending had dropped to an average of about 25 each day. M’Laren commented: “Those who come, however, seem really fond of school, and are making progress in reading, sewing, and writing: they have committed some hymns and passages of Scripture to memory, and I do hope that the seed which is now attempted to be sown in much weakness, may be the commencement of a great work amongst these poor, degraded, ignorant but interesting children.

“There are some promising girls who attend very regularly: of them I have made monitors, and hope some of them will ultimately become native teachers.”

She recognised that it would not be possible to set up orphanages for destitute children as in India. She explained: “Children are much thought of, and when a parent dies, and leaves a family, they are soon adopted by another, who regards them as his own.

“They are a free people and do not like anything like restraint or servitude. When they do engage as servants, it is only for the cows which they expect; and when their time is expired, they are glad to get back to their kaross and their entire freedom.”

To Miss M’Laren and the other SPFEE agents who went to South Africa education was the lever by which the Africans would be raised from “their present barbarous state, and make them industrious, useful and happy.”

The SPFEE expected that teachers like Miss M’Laren would materially contribute to the advance of civilization in South Africa. And, like Robert Moffat (1795-1883), the Scottish missionary who worked in South Africa from 1817 to 1870, believed that only through Christianity could slavery be stopped in Africa.

Miss Hanson, the SPFEE’s first agent in South Africa, wrote from her school in Cape Town in April 1838: “We owe it to much injured Africa – it is the least we can do as a reparation for her wrongs – to send those who, when the body is no longer enslaved, shall free the mind from that thraldom in which it has so long been kept.”

But the belief that the Africans could be educated and be treated as equals would constantly create conflict between the Protestant Missionaries, the first of whom to arrive in South Africa were the Moravians.6 The first LMS missionaries, under the leadership of the Dutchman Johannes van der Kemp experienced this very soon after their arrival in South Africa in 1799.7

By then Cape Town Colony had grown considerably since the Dutch East India Company had started using it in the mid 17th century as a supply post for its ships on the spice route to Indonesia. The Company had encouraged Cape colonists to develop farms as the local tribes, the Khoikhoi and the San (known collectively as the Khoisan) did not want to trade with it. It also brought in slaves from Madagascar and Indonesia to supply the settlers with cheap labour.8 The Khoisan were driven off their pastoral lands, their cattle were stolen, and many died either due to the diseases introduced by the foreigners or from armed conflict with the Boers.9

Van der Kemp and another LMS missionary, established Bethelsdorp near Port Elizabeth in 1803 as a refuge for those Khoikhoi who wanted to escape the bonded labour form of slavery that the Boers had inflicted on so many of them. He, like Dr John Philip who became the resident director of the LMS in South Africa in 1919, earned the everlasting contempt of the Boers for treating the Africans as equals, and seeking to provide them with education and vocational skills so that they would not be forced into any form of slavery.10

In 1826 Philip made the first of his two visits to London to fight for the civil rights of the Khoisan arguing that they should have the same protection by law as the colonists. In the preface to his book, Researches in South Africa (published 1828) he summed up so well the way missionaries at that time were unable to dis-entangle the Christian message with Western imperialism and capitalism.

The Christian concept of being transformed into the spiritual image of Christ became confused with the expectation that all should conform to European culture and dress. I doubt that the missionaries realised how much their views were shaped by the discourse that pervaded Britain and Europe at that time. In fact they became part of the strong narratives which developed that discourse.

They probably found it very exciting that missionaries like Moffat were lauded as pioneering heroes of the British Empire. Miss M’Laren would play her own small part as a heroine in “darkest Africa”.

And so Philip wrote: “While our missionaries, beyond the borders of the colony of the Cape of Good Hope, are everywhere scattering the seeds of civilisation, social order, and happiness, they are, by the most unexceptionable means, extending British interests, British influence and the British empire.

“Wherever the missionary places his standard among a savage tribe, their prejudices against the colonial government give way; their dependence upon the colony is increased by the creation of artificial wants; confidence is restored; intercourse with the colony is established; industry, trade, and agriculture spring up; and every genuine convert from among them made to the Christian religion becomes the ally and friend of the colonial government.”

He also wrote that the missionaries had found that the Africans in Cape Colony had been deprived of their country and been reduced to slavery. He added: “The missionary stations in South Africa are the only places where the natives of the country have a shadow of protection, and where they can claim an exemption from the most humiliating and degrading sufferings.”

He believed that the Khoisan had a right to a fair price for their labour; to an exemption from cruelty and oppression; to choose the place of their abode; and to enjoy the society of their children.11

David Livingstone, who arrived in South Africa in 1841, reported that to the Boers Africans were just “black property” whom they could kill or force into bonded labour as they pleased.12

Philip’s daughter, Elizabeth (Eliza) Fairbairn was the SPFEE’s correspondent in South Africa and the Society continued to send teachers after Miss M’Laren completed her engagement with it in 1844. By then M’Laren had trained a girl called Utali to teach at the school at Igqibigha. She commented that this showed that the Xhosa girls were teachable.

Africans would be dependent upon Christian missions for their education until the mid 20th century and many were trained to become teacher evangelists.13 Girls formed the majority of those attending the mission-run elementary schools and by 1868 the school at Lovedale was offering the same advanced education to African girls as it did for European girls.14

When the school at Lovedale was founded in 1841 the initial focus had been upon ‘industrial training’ in agriculture, masonry, carpentry, blacksmithing and wagon making. Initially it was believed that Black people could best be elevated by providing higher education for a few but after 1875 the emphasis was on the education of many.15

©P Land 2014

Sources and notes:

The illustrations of Cape Town and of waggon travel in South Africa are from Robert Moffat, The Missionary Hero of Kuruman by David J Deane, Fleming H Revell Company, New York, Chicago and Toronto, 1880

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15379/15379-h/15379-h.htm

1 The main source I have used, including the spelling of Miss M’Laren’s name, is The History of the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East, published by Edward Suter, London, 1847, pp 162-179.

John MacKenzie in his chapter ‘Making Black Scotsmen and Scotswomen’, in Empires of Religion (Ed Hilary M Carey, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2008), states that the Scottish Ladies’ Kaffrarian Society sent a Miss McLaren to South Africa in 1939 (p126). As usual with such 19th century ladies’ societies there is no mention of her first name.

2 Rebecca Irvine Olgilvie, daughter of Thomas and Isabella Ogilvie of Glasgow, married the Rev Robert Niven at St Andrew’s Presbyterian church, Cape Town, on Wednesday, November 27, 1839. South African Commercial Advertiser October to December 1839, transcribed by Sue Mackay

http://www.eggsa.org/newspapers/index.php/south-african-commercial-advertiser/176-saca-1839-oct-dec

Niven was minister at Maryhill Church, Glasgow, from 1856 until he retired in 1877.

3 The frontier wars continued until the British gained supremacy in 1879. The seventh frontier war was from 1846 to 1847, and the next was in 1850 during which Niven and his wife had a narrow escape when another mission he had founded, at Uniondale, was destroyed.

4 A Narrative of a Visit to Mauritius and South Africa by James Backhouse (1794-1869), Hamilton, Adams and Co, London, 1844. Available on Google Books. Pp226-227.

5 A kaross is a cloak made from the hide of an animal with the hair left on.

6 The first Moravian missionary to South Africa was George Schmidt (1709-1785) who was there from 1736 to 1744. His baptisms of five converts in 1744 were condemned as illegal by the Dutch clergy and he was forced to leave. Three more Moravian missionaries were sent in 1792, and restarted the mission, assisted by Vehettge Magdalena (Lena) Tikhuie. She was one of those converted by Schmidt and had acted as a church leader in the absence of any missionaries.

The new missionaries created the town of Genadendal (“Valley of Grace”) where Schmidt had worked. This became a model town with schools and where the Africans could learn vocational skills to enable them to become self sufficient. There was much opposition from the Boers to whom the Africans were “children of the devil, black ware and black cattle”. In 1995 Nelson Mandela changed the name of the president’s official residence in Cape Town to Genadendal.

J E Hutton, A History of Moravian Missions, Moravian Publications Office, London, 1922, pp128,179-180,266-270.

And about Lena Tikhuie: Dictionary of African Christian Biography.

See also : http://www.viewoverberg.com/Genadendal.asp

7 In his book A History of Christian Missions in South Africa (Longmans, Green and Co, London, 1911 ) the South African historian, Johannes du Plessis (1868-1935), described how van der Kemp (1747-1811) had been so affected by studying the works of the 18th century Enlightenment philosopher, John-Jacques Rousseau, that he believed that Africans were equal to white men. Plessis wrote: “No responsible missionary today would venture to preach or to practise the doctrine of social equality between the white and the coloured races.” pp217-128 Thankfully missionaries like Trevor Huddleston (1913 – 1998 )did not agree with him.

See http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/father-trevor-huddleston

8 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_South_Africa

9 Researches in South Africa by The Rev John Philip DD, James Duncan, London, 1928, Vol I pp2-5 and Vol 2 p2610

James Cappon, Britain’s Title in South Africa, 1901, p321

http://archive.org/stream/britainstitleins00cappuoft/britainstitleins00cappuoft_djvu.txt

11 Researches in South Africa: Preface Vol 1 ix-x; xxvi; xxx-xxxi

12 In 1852 Boers attacked Livingstone’s mission station, killed all the African men and carried off 200 school children into slavery. The Boers also destroyed Livingstone’s home, and took his furniture and clothing to meet the cost of the attack. David Livingstone Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, John Murray, London, 1857, pp38-39 (Chapter 2) Google Books or

see http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/l/livingstone/david/mission/chapter2.html

13 Horton Davies & R H W Shepherd (Eds) South African Missions 1800-1950, an anthology Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, London, 1954. P xix

14 1855-1863: A Dividing Point in the Early Development of African Education in South Africa, a paper by R Hunt Davis Jr

15 see Lovedale Public Further Education and Training College