When Sophia Cooke took over running the Chinese Girls School in Singapore Mary Ann Aldersey (艾迪綏) was already a famous role model for those women who were interested in missionary work overseas. And, amazingly, she became an important role model for Chinese girls. Two of the girls Miss Aldersey inspired became the first Chinese female schoolteachers in China: Ruth Ati ( who married Tseng Lai-sun 曾来顺- also known as Chan Laisun or Zeng Laisun ) and Christiana A-Kit (who married Kew Teen-shang) . The British women who worked with her were Mary Leisk Russell (who became the wife of Bishop William Russell of North China), and Burella and Maria Dyer. Maria Dyer married James Hudson Taylor (戴德生) and with him founded the China Inland Mission.

Mary Ann Aldersey was the most independent and probably the most stubborn of all the single women who went overseas to found girls’ schools during the mid 19th century. She studied Chinese for years but never did become fluent in the dialect she most needed. Nor did she have much respect for Chinese culture. And yet she was obviously a great inspiration to many of the Chinese girls she taught. And it was, I believe, due to that that she was able to start what was most likely the first school for girls in China – at Ningbo in 1843.

For she travelled to China with three teenage girls: her ward, Mary Leisk (daughter of a Scottish merchant) and two Malay-Chinese girls whom she called Ati and Kit. She had taught Ati and Kit in Surabaya in Java and they had run away from their homes to join her when she left for China. It was these three girls who learnt the Ningbo dialect so well. And it was probably the presence of Ati and Kit at the Ningbo school which reassured parents that the strange white woman would not kill their daughters.

It had taken Miss Aldersey almost 20 years to reach the country to which she believed she had been called by God to work in. Picture : Mary Ann Aldersey as a young woman.

She was born in what was then the leafy London suburb of Hackney on June 24, 1797 and later attended the congregational church where her father, Joseph, was a senior elder. By the time she was 19 she was involved in Christian outreach in a nearby working class area even though at times she was pelted with stones. Her mother died when she was 25 and her father expected her to manage his household and look after him.

And then, in 1824, Robert Morrison arrived in London. He had become famous as the first protestant missionary to China having managed to live in the foreign factory area of Guangzhou (Canton), learning the language and then working as a translator with the British East India Company. During the two years he was in Hackney he taught Chinese to both men and women who were interested in going as missionaries in China. It was at those classes that Miss Aldersey met Maria Tarn, the daughter of one of the directors of the London Missionary Society (LMS). Maria later married another of Mr Morrison’s students, the Rev Samuel Dyer.

Miss Aldersey became equally convinced she was called to work among the Chinese but her father refused to give her permission to go. So instead she had made a donation to the LMS to induce it to send two single women to Melaka. One of those two women, however, according to the LMS, showed symptoms of insanity due to studying Chinese and so the Society sent just Maria Newell, on the same ship as Maria and Samuel Dyer in August 1827. Miss Aldersey was determined that Miss Newell should have a single woman working with her. So as a member of a ladies’ committee of the British and Foreign Schools Society she travelled to Edinburgh where she was introduced to Mary Christie Wallace who was sent to Melaka in 1829 (See The Saga of Miss Wallace).

In 1832 Miss Aldersey’s father did finally give his consent for her to fulfil her calling but then her sister-in-law died and she was expected to care for the eight motherless children. “So with deep regret and bitter disappointment I gave up my longed-for work abroad,” she wrote later. She did, however, pay for a Chinese tutor (dressed in a flowered silk robe) to come to her brother’s house in Chigwell Row, so that she could continue her language lessons. She also learnt a lot about how to care for children but when a friend commented that she should be so happy to be among so many nieces and nephews she retorted: “I would rather be in prison with Chinese children around me.” She often went to her room to cry in frustration and depression.

With her experience in sending single women overseas she was invited, in July 1834, to join the newly-formed Society for Promoting Female Education in the East (SPFEE) and immediately encouraged the committee to set aside £50 to support Miss Wallace. But when she asked SPFEE to return that money in April 1837 the committee agreed “it should be appropriated to her benefit under her affliction”. It can only be assumed that they thought she was ill-advised to go overseas herself at the grand old age of 40, especially after what had happened to Miss Wallace. But by then Miss Aldersey was determined to go. Her brother had just announced that he was getting married again and so she felt free at last to book her passage on an eastward bound sailing ship. She recognised, however, that there were still some hurdles to overcome.

She noted: “It was manifestly of great importance that nothing should be entered on by me with precipitation especially as the subject of single ladies engaging in foreign missions either with or without the control of a committee was not generally approved.”1 And so she submitted to a medical examination to prove she was not mentally unstable. And probably to prove to the SPFEE that she was not under any affliction!

On August 10, 1837, she joined some SPFEE agents on the brig Hashemy at Gravesend. They were chaperoned on the journey by the LMS missionary , the Rev Walter Medhurst and his wife, Eliza. Miss Aldersey would never accept the leadership of any man from then on but she did respect Medhurst and it was he who encouraged her to go to Surabaya in Java. At first the Dutch rulers in Java considered forcing her to live in Jakarta (Batavia) but were convinced that a woman missionary wasn’t likely to do much harm.

In Surabaya she lodged with a Dutch Christian clockmaker for six months and then moved out of the European quarters so that she could organise a school for Malay Chinese girls. Very few families were willing to allow their daughters to attend her school and if they did it was only on the condition that the girls remained secluded and well protected.

Ati (then about 12 years old) and Kit were among her first students and the former was especially keen to learn to read. Ati was so inspired by Miss Aldersey that her mother became very angry and even threatened to kill her. It was likely that both girls faced persecution because they wanted to become Christians and so Miss Aldersey planned not only to leave for Hong Kong with 14-years-old Mary Leisk but also devised an escape route for the two girls which involved walking at night to the home of a foreign Christian family.

She wrote later:“They had themselves determined to escape (but) as young Chinese females never walk out, except perhaps the distance of a few doors, my two pupils knew nothing of the way to (that) house. I therefore drew a plan which would assist in tracing out correctly the course they ought to pursue. Their great difficulty, however, had reference to their starting. They did not live in the same house or the same street. Neither knew on what night, much less what hour, the other might start for her hazardous exit.” Ati made two unsuccessful attempts before, on the third, she managed to meet up with Kit.

To disguise the fact that they were two young girls who would not be allowed to leave their homes Ati was dressed as a Chinese lady and Kit as her Javanese servant. By dawn they were very weary as they were so unaccustomed to walking. As the sun rose they thought one of their parents would find them but did at last locate the house they were searching for.

Their parents put up posters about the missing girls in Jakarta and kept watch on the houses where they thought Ati and Kit might be hiding. The girls, at their request, were baptised by the Rev Medhurst before they travelled to Singapore. Miss Aldersey and Mary, had, however, already left Singapore for China, first to Macau and then to Hong Kong.

In Singapore Ati and Kit stayed with Charlotte and Benjamin Keasberry and became friends with Hanio and Chunio who were studying at the Chinese Girls School CGS) started by Maria Tarn Dyer. They reached Hong Kong and were reunited with Miss Aldersey on Christmas Day 1841 – seven months after their daring escape from their homes in Surabaya.

In April 1846 Ati wrote to the SPFEE: “We are very much interested about Chunio and Hanio. We knew them both before they were converted, and when we had news from them, that they had become the disciples of Jesus, it astonished me very much, it was as news from heaven; for we were so lonely, because there was none of our sex who are Christians which we knew, besides us two , my companion and I: therefore when I heard about them, it was a great comfort to me to have other fellow-travellers to heaven-ward. Though we are far from each other, we have correspondence with them, and we can comfort each other in letters.”2

By then the SPFEE was so impressed that Miss Aldersey had managed to set up a girls’ school in Ningbo that it did send a small grant. Some male missionaries had been less impressed and described Miss Aldersey as “quixotic” because she had “waited for no protection but went straight to Ningbo and there established her school.” 3

She had soon became notorious in Ningbo. The Chinese whispered: “All English children have blue eyes, with which it is, of course, impossible to see, and the strange lady wants to receive our children, only that she may pick out their eyes, and send them as a valuable present to her friends at home.” Rumours were spread that she had massacred children and their parents. She was even accused of eating children2.

When, as part of her daily exercise programme, she walked the city walls during the dark winter mornings, led by a servant carrying a lantern, it was believed she was conversing with the spirits of the night. Not surprisingly those who visited her were too scared to eat the food and drink she offered them, especially as it was said she had a special drug which could turn them into Christians. A small book for children published in London in the 1950s about her was entitled The Witch of Ningpo.

Without Mary, Ati and Kit she would never have succeeded. She wrote: “The two dear young converts who have followed me to this country have proved most valuable assistants, not only, or perhaps principally, in the amount of work done for me with reference to the school, but also in gaining for me the confidence of the people, who are still greatly prejudiced against foreigners, having formed for me a sort of link between the people and myself, they being Indo-Chinese, and adopting the costume of this province.”4 Of Mary it was later said: “She not only spoke like the natives, and understood every shade of their vernacular idiom, she felt with them and thought with them.” 5

On arrival in Ningbo in 1843 Miss Aldersey had rented half of a wooden house on the river bank outside the city for her first school. She had then moved to a large house in the city and set up a boarding school for about 50 girls. As at the CGS in Singapore the parents had to sign contracts binding them to keep their daughters at the school for set periods of time.

Miss Aldersey explained to the SPFEE that she had taken on so many girls because she realised that once one was converted to Christianity many parents would take their girls away. When that did happen many parents chose to leave their daughters at the school because the girls were either dull or diseased. (There were the exceptions, however, and one of those was San Avong – see Mary Ann Aldersey’s Mission )

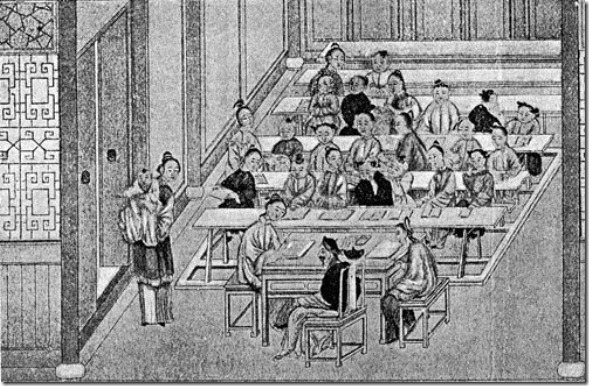

Below: The schoolroom in the Ancestor’s Hall at Miss Aldersey’s rented house in Ningbo. The Chinese teacher is seated in front, with Kit and Ati on either side of him.

Two of the men Miss Aldersey employed were converted and, once they had received Bible training, she sent them on evangelistic trips into the surrounding countryside where the foreigners were not then allowed to go under the terms of the 1842 treaty. Like Sophia Cooke at the CGS in Singapore Miss Aldersey shared the vision for mission with those at her school who became Christians and over the years that would develop into a considerable amount of outreach work.

But she also developed another career – that as a matchmaker. She may have been determined to stay single herself so that she could be a missionary, but she seemed equally determined to organise the lives of the girls who worked with her. By 1852 she had arranged marriages for Kit, Ati and Mary.

Kit (Christiana A-Kit) married Kew Teen-shang In December 1847. He had attended a mission school in Jakarta and was baptised in Shanghai in November 1845. In 1848 Miss Aldersey wrote to the London Missionary Society (LMS) that he was working as a printer for that mission in Shanghai. She added that this was the first marriage of two such converts in that region6. It is likely that Kew Teen-shang also undertook evangelistic journeys for Miss Aldersey recorded in July 1851 that he had just returned from his second visit to Hunan Province and brought back with him two Jews and five rolls of the Jewish Law.

Ati (Ruth A-Tik) married Tseng Lai-sun in July 1850. He came from a poor family in Singapore and after he was converted to Christianity was sponsored by missionaries to go to the USA for his education. Afterwards he worked with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in Guangzhou until 1853 when he moved to Shanghai and, thanks to his language skills, had a varied career as a businessman, and then with the Fuzhou Naval School and the Chinese Educational Mission before becoming the chief private English secretary to a Chinese viceroy. Of the couple’s six children one son became a very successful journalist (Spencer 曾笃恭 ), another (Elijah 曾溥 )was probably China’s first “scientifically trained engineer’ after studying in Germany, and two of their daughters married Westerners. The eldest of those was a founder member of the Chinese Red Cross Society.7

In early 1907 Mrs Lai-sun (pictured above – with thanks to Mary Severin, see comment below) was the honoured guest at the day devoted to Women’s Work during the China Centenary Missionary Conference in Shanghai. In the official report of the conference it was stated that she was introduced as the oldest living example of women’s work for Chinese girls and as “the first of that noble band of women who had devoted their lives to women in China”. 8 She died in January 1917 aged 92.

Mary Leisk married the Rev William Russell in September 1852. They spent most of their married life based in Ningbo and never had any children. He was consecrated Bishop of North China in December 1872 and died in October 18799. His widow continued working among Chinese women in Ningbo until her death in August 18875.

After Kit, Ruth Ati and Mary were married Miss Aldersey recruited two more teenagers to help her – Maria Tarn Dyer’s daughters Burella and Maria. Most of the girls who came under Miss Aldersey’s influence did accept her guidance as can be seen in the stories of San Avong, Asan and also of Agnes Gutzlaff. But not Maria!

copyright Pip Land December 2012

WAS YOUR FAMILY IN CONTACT WITH BRITISH CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES IN THE 19TH CENTURY? If so why would you like any research done concerning those missionaries: when and how they reached your family’s home town, what they did there and maybe even if they had contact with your ancestors? If so post a comment on this website.

For photos of Ruth Ati see:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/76788493@N00/sets/72157603097655825/

And http://www.facebook.com/pages/Zeng-Laisun/177618995623588

Sources:

E Aldersey White A Woman Pioneer in China, The Livingstone Press, London 1932. Both pictures come from this book.

Minutes of the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East, in the Special Collection at Birmingham University Library.

J Reason, The Witch of Ningpo – Mary Aldersey of China, Eagle Books, No 30, Edinburgh House Press, London, 4th impression 1956 (price one shilling)

plus –

1. From a letter to Miss Aldersey’s nieces, in China Odds Box 8 of the archives of the Archives of the Council for World Mission (CWM),School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

2. E J Whately (Ed) Missions to Women of China, James Nisbet, London 1866, pp98-99

3. The Chinese Missionary Gleaner, (CMS)June 1857, p94.

4. Missionary Register 1847, p 116 – report of the Eastern-Female Education Society 1847, p116

5. The Church Missionary Intelligencer December 1887 (CMS), p 744

6. Miss Aldersey’s letter to the London Missionary Society, in the China Odds Box 8, CWM archives at SOAS.

7. Carl T Smith Chinese Christians, Oxford University Press 1985, pp69-74

for more about Tseng Laisun also see Chinese Educational Mission Connections 1872-1882 – The CEM Staff:Three Notable Figures – www.cemconnections.org

8. Centenary Conference Committee, China Centenary Missionary Conference (April 25 to May 8, 1907), Shanghai, 1907. Also see the newspaper report in the Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, 5 July 1907, p6, available on-line through the National Library of Singapore.

9. The Church Missionary Gleaner, April 1888 pp51-52

Hello Pip, By chance, just recently, I discovered the Zeng Laisun facebook page and the link to this webpage. Just to introduce myself, Ruth Ati was my great-great grandmother. I am descended from Ruth’s daughter, Lena, who married Will (?) Buchanan. Lena had two daughters, Ruth Buchanan (my grandmother) and Eulalie. As a family we knew nothing of this until my maiden aunt died in 2007. My cousin, Diana Mackay, and I discovered in her attic a treasure trove of diaries and pictures(some of which I posted via Flickr, which you have seen). The picture of an elderly Ruth Ati was sent by her to my grandmother which says ‘to Ruth with grandma’s dear love’. I am not sure who has written the Tsen Laisun facebook page, do you know who he or she is? I am also related to Lawrence Walls, because my grandmother Ruth Buchanan married David Mackay, who was related to the Walls family via his mother. My family are a little puzzled who it can be! Please feel free to contact me if you wanted more information about Ruth Ati’s descendants through her daughter. Kind regards, Mary

Hi Pip and Mary. I just discovered this website and fascinated to read about your research on Aldersey’s school in Ningbo. I am doing a PhD in modern Chinese history and my research focuses on how Chinese women experienced mission education. I have done some previous research on how Aldersey’s school evolved in the late 19th and early 20th century in China. Mary – fascinating to hear about your family connection to Ruth Ati. I would love to hear more about it if you would like to get in touch! Thanks for creating such a great database of stories on pioneering women’s education Pip. Best wishes, Jenny.

Hi Pip, I am doing a degree in History at Lancaster University and was wondering about doing my dissertation on Mary Anne Aldersey and her role in the Christian mission and women’s education in China and was wondering if you would mind me looking up and possibly using some of the same sources that you have used. Would be grateful for any help you could give me with this, thanks for creating such a wonderful database!

Best Wishes, Millie.

I am Christine,I was born in Ningpo where Mary Ann Aldersey devoted herself for Chinese girls education.By accident,I was reading the female missionaries’ stories post by my pastor on social media and found that there was a female missionary from British who was living in my hometown about one hundred year ago.Immediately I was seeking for more information about Mary and eventually I got this article!My high school is named Ningpo NO.3 Middle School whose name was transformed form “The Trinity”,because this school initially was established by the British Church Mission Society and at that time it was a girls school in Ningpo.I am so moved by Mary’s story of Ningpo and thanks for this excellent article to know more about this great women.