Left: A baby rescued from a drain in Singapore in 1883 and given to the Chinese Girls’ School (FMI). Ah Tu, who was one of the CGS graduates to go as missionaries to China in 1878, was also rescued from a drain.

By the 1870s the Chinese Girls’ School in Singapore (now St Margaret’s School) was renowned for not just educating Chinese girls but for taking in babies plucked from the gutters, caring for orphans and providing a home for those saved from slave ships. It was also an excellent “marriage bureau” for Christian Chinese men from Singapore to Australia. But that was not enough for Sophia Cooke. She wanted to expand the mission work of the school and its graduates to China.

The school’s wayfinder for this was Miss Houston who retired from its Ragged School work and, at the request of a Church Missionary Society clergyman, went to Fuzhou in April 1875, to supervise a Christian girls’ boarding school there. This would lead to the CGS sending eight young Chinese women as missionaries to Fujian Province in China.

They would often find themselves in very dangerous situations for resentment was building up in China against foreigners and those associated with them. Not surprisingly the Chinese were deeply offended and angry about how the British and other Western nations had used their superior firepower to force unfair treaties and the trade in opium on China following the Opium Wars between 1842 and 1860. Most Christian missionaries were also offended by the opium trade but were delighted that those treaties provided them with the opportunity to at last work in China. The Treaty of Nanking in 1842 only allowed foreigners to live and work in the five treaty ports of Shanghai, Ningbo, Guangzhou (Canton), Fuzhou (Foochow) and Xiamen (Amoy) but some missionaries constantly broke the rules and went further inland.

Most of the missionaries had little appreciation of Chinese culture as they were so convinced about the superiority of their own to the point that they confused Christianity with Westernisation. They expected Chinese converts to break with traditional customs such as idol and ancestor worship and helping to support the temples. This led to social upheaval and created more resentment – and when the missionaries called on the foreign consuls for assistance even more Chinese became aware of their nation’s humiliation at the hands of these hated “barbarians”. As the years went by the full impact of China’s “9/11 moment” in 1842 became more and more apparent especially as foreign missionaries began itinerating outside the treaty ports.

Chitnio, the first CGS graduate to be officially sent to China1 very quickly learned that national Christians in China faced a lot of persecution. She spent ten years at the CGS after being enrolled as a student when she was a nine-years-old orphan. Following her conversion to Christianity she recounted that her relatives had given her up and so she stayed at the school. By 1876 after praying about joining Miss Houston in China a Chinese Christian, the Rev Ling Sieng Sing, travelled from Fuzhou to Singapore to marry her.

Soon after her wedding in October 1876 she described how her husband had been treated several years earlier when he had been sent by the CMS with three others to a large town in Fujian province. The local people were furious that Christians had rented a house and begun to preach there. The four men were seized, bound with ropes and hung from a tree, either by their pigtails (as Chitnio recorded) or by their thumbs2. They were intensely humiliated in other ways and thrown out of the city. Chitnio explained that the chief men in the town were afraid that more would become Christians and that the English would come and take over.

Miss Cooke had planned to send another CGS graduate to Fuzhou with Chitnio and her husband but was told it was not culturally acceptable for a single woman to accompany the young couple. So Wee Inn had to wait until late 1877 when Miss Cooke found a sea captain who could be trusted to care for her on the journey. She was the second single Chinese woman to be sent as a missionary to China3. Wee Inn had been rescued from slavery in early 1858 and, like the others who had no parents or family, was raised as a Christian at the school by an older girl who acted as her surrogate mother.

Both she and Chitnio were in Fuzhou when the CMS buildings there were destroyed in 1878. Miss Houston told the SPFEE: “Five days ago the Chinese attacked us, pulled down, and burnt to the ground acres of our houses, and we had to escape for our lives. I cannot write to you all about it now, my heart and brains will not let me. It seems all like a dreadful, confused dream. Thank God no lives were lost. Inn and Chitnio are safe and well. This last trial seems to have added ten years to my age.” That attack led to the CMS mission being moved out of the centre of Fuzhou to a suburb called Nantai.

The missionary who had asked the CGS for help with mission work in Fujian, the Rev John R Wolfe, was so impressed by Chitnio and Wee Inn that he requested even more CGS graduates to be sent. After the mission in Fuzhou had almost collapsed in the early 1860s he had come to depend upon an enterprising and often courageous group of national believers even though he was criticised by other missionaries for doing so. He knew that these young Christian men needed the support of educated wives like Chitnio and Wee Inn (who married soon after she arrived in Fuzhou). So, in December 1878, four more were sent to Fujian.

The mission was well prepared for, on their arrival, their prospective husbands were awaiting them! Miss Houston reported that Jim (Patience), Choon, Sein and Ah Tu, arrived on a Friday and were married on the following Monday. “They were very well indeed, and exceedingly happy. They have seen their husbands, and said ‘Yes Sir’ when they were asked by Mr Wolfe: ‘Will you have this man for your husband?’ Their husbands are all such thoughtful, good men. They have brought their wives such a nice suit of clothes to be married in, so they will not want to hire a dress. I feel just what a mother must at losing four daughters at once.” All four went to live with their husbands outside Fuzhou and must have experienced a considerable amount of culture shock. At the CGS they had lived in a very protected environment where they could even play crochet on the school lawn. In rural Fujian life for them would be tough and often very lonely.

A month after those weddings Miss Houston informed Miss Cooke : “I don’t know how to tell you the sad news, but it must be told. Our dear Chitnio is left a desolate widow. My heart aches for her.” Chitnio was taken on as a biblewoman by the CMS at Fuzhou and Miss Houston reported: “She is working away, going about all the streets of the city, and visiting the houses, contrary to all Chinese rules of propriety. Her dear little baby (son) is a great comfort to her, and goes a great way towards filling up the empty void that was left in her poor heart”. According to the Church Missionary Review in 1912 the Rev Ling, having never got over the shock of how he had been humiliated years before, had “lost his reason” and taken his own life. It seems that Chitnio never mentioned that in her letters to Miss Cooke.

Left: Chitnio with her son in 1883

Chitnio was not the only one from Singapore to face hard times. Sein’s husband took her back to a village, about ten days journey from Fuzhou, where he too had been beaten, robbed and thrown out for being a Christian. Miss Houston commented: “He is a good, brave young man, and he not only dared to go back himself but took a wife with him.” Sein, however, had great difficulty learning the local dialect. (At that time the dialects in Fujian differed considerably between each valley.) In the first few years of her married life their Christian chapel was burnt down twice and during the second attack she fell ill and died.

In an obituary to her Miss Cooke recalled how Sein had been sold by her mother in China to Malay sailors and brought to Singapore in 1858. The police took possession of her and the other girls on the ship and delivered them to the CGS. There Sein not only became a Christian but also the leader of the choir as she had such a lovely singing voice.

Wee Inn was at first based at the girls’ boarding school in Nantai where the pupils helped her with the language. Later she moved with her husband to Huashan, a small hill station near Gutian (Kucheng). Another Englishwoman, Miss Foster, was sent by Miss Cooke to help at the boarding school in Nantai but then Miss Houston was forced to leave due to ill health. She had never fully recovered from the attack on the mission in 1878 and returned to England in 1880 where she died some months later. Miss Foster then appealed to the CMS but that mission was not yet prepared to send single women as missionaries. So the SPFEE sent Jessy Bushell4 in 1883 to help run the girls’ boarding school. That school was by then taking only girls from Christian families.

It was a Chinese woman and her daughters who went back into the centre of Fuzhou and opened a day school for non-Christians. That was Lydia, the wife of the Rev Wong Kiu-Taik, who was ordained in 1868. He was a catechist with the CMS in Fuzhou when the Rev Wolfe arrived in 1862. The CMS mission in Fuzhou had failed to thrive since it began in 1850 and again came close to closure when Wolfe became very ill and went to Hong Kong to recuperate in 1863.

While in Hong Kong Wolfe heard of Lydia and her family. Her parents had converted to Christianity and in 1860 sent their two daughters to the newly formed Diocesan Native Female Training School. The sisters were baptised in 1861 and Lydia stated: “I believe that God’s Holy Spirit has been given to me. I feel a light shining in my heart which tells me what is right and what is wrong.” While Wolfe was matchmaking in Hong Kong Wong Kiu-Taik took care of the small fellowship of believers associated with the CMS in Fuzhou. He then travelled to Hong Kong to marry Lydia in January 1864. The only way he could communicate with his future father-in-law was by using written Mandarin.

His bride had such tiny bound feet that she had to be supported by Sophia Baxter5 during the wedding service in Hong Kong cathedral. In Fuzhou Lydia not only had to adjust to married life far away from her family and learn the local dialect but also helped to encourage and support that small group of believers when they came under attack before Wolfe and his wife returned.

It wasn’t long, however, before Lydia had started a girls’ school in Fuzhou. When Miss Houston arrived there were 12 students, all from Christian families, and the premises were becoming too small. She described how the school was flooded when the river overflowed in 1876. Many of the girls were up to their shoulders in water as they escaped with some of the smallest children clinging to the backs of the older students. They made a raft so that they could float their luggage through the streets.

While Lydia’s vision was for the girls of Fuzhou Wee Inn’s, in 1885, was for Korea. The churches in Fujian sent two couples as missionaries to Korea that year. The other woman in the team was Tek Lim who, who with another CGS graduate, had only recently arrived in China. The two couples were, however, very restricted in what they could do and the Koreans were too scared to become Christians as the King would have had them killed. So within a few years they returned to Fujian.

By then the team of foreign missionaries in Fujian had grown to include Robert and Louisa Stewart from Ireland and several single women. The attitude of mission societies was changing and by the 1890s two thirds of the missionaries in China were women. One of those in Fujian was Elsie Marshall, the daughter of an English vicar. She was 23-years old when the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society sent her to China in 1892.

She spent the first year in Fuh-ning and was so successful in her language study that she was soon involved in missionary work. That included going with Patience (Jim) to a nearby village. There she was struck not only be the abject poverty of those they visited but how hard it was for such Chinese to understand the Christian faith, even when Patience explained it so simply.

In January 1894 she joined the Stewarts at Gutian and a month later was assigned an area to work in. Travelling was very difficult in that region at that time and on occasions she walked 15 to 21 miles a day accompanied by only a Chinese coolie. She often visited villages and Christian families with Topsy Saunders , one of two Australian sisters in their team6. On December 24, 1894 at Gutian she wrote : “One more Christmas nearly gone – one year nearer to heaven.”

On August 1, 1895 she, the Saunders sisters and the Stewarts with some of their children were among eleven foreigners massacred by members of the Vegetarian sect7 at Huashan. In one of the last letters she wrote before her death Miss Cooke sadly commented that the Singapore girls were closely connected with those who had been murdered. But for Chitnio, Wee Inn and the others in Fujian it was business as usual.

Chitnio was assisting with training biblewomen and accompanying foreign missionary women on their visits to villages. Miss Bushell visited Wee Inn (wife of the Rev Yek Sui Mi) in Fuqing (Hok Chiang) in 1897 and found her as busy as ever. Wee Inn had three sons and one daughter and Miss Bushell commented: “Her family is quite a model of good behaviour, brought up carefully and nicely. She is certainly a most earnest and good woman – her light shines brightly.”

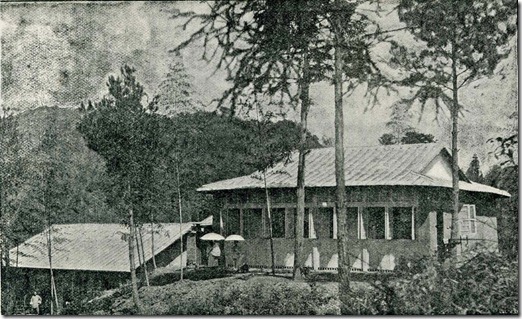

Above: The mission houses at Huashan. The Stewarts were in the upper one and the single women in that below it. (From ‘For His Sake’)

copyright Pip Land October 2012

WAS YOUR FAMILY IN CONTACT WITH BRITISH CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES IN THE 19TH CENTURY? If so why would you like any research done concerning those missionaries: when and how they reached your family’s home town, what they did there and maybe even if they had contact with your ancestors? If so post a comment on this website.

SOURCES:

Female Missionary Intelligencer 1861-1896 – the picture of Chitnio and her son was first published in the Church Missionary Gleaner and then in the FMI in March 1883. Pictures from the FMI have been reproduced with the permission of the British Library.

E A Walker Sophia Cooke, Elliot Stock, London 1899

The Church Missionary Gleaner, CMS 1889 and 1894

For His Sake, Extracts from the letters of Elsie Marshall, The Religious Tract Society, London 1897

Notes:

1 – The first CGS graduate to go to China was Kai-Chai, the youngest sister of Chunio and Hanio (mentioned in St Margaret’s School – the early years, and Sophia Cooke’s Mission. She married a Christian from Jakarta and they went to Hong Kong.

2 – CMS Church Missionary Review 1912

3 – The first single Chinese woman to be sent by a mission to China was Agnes Gutzlaff – in 1856. She was one of the blind girls adopted by Mary and Karl Gutzlaff and sent to England for education. She was the only one to return to China. See Mary Ann Aldersey’s Mission

4 – In 1889 Jessy Bushell became the first woman to address the Fujian Provincial Church Council when she gave a speech in Chinese pleading for the abolition of early and compulsory marriages for girls. (The Church Missionary Gleaner, May 1889).

5 – Susan H Sophia Baxter (1828-1865). She set up several schools in Hong Kong and these became known as the Baxter Vernacular Schools.

6 – Elizabeth (Topsy) Saunders and Eleanor (Nellie) Saunders were the first women to be sent to China by the Church Missionary Association of Victoria, Australia.

7– The Vegetarians (Tsai Hui) was a Buddhist group which took a vow of vegetarianism. It became particularly powerful in Fujian between 1892 and 1895. Seven of those who carried out the massacre on August 1 were executed in September that year.