One of the pioneering women who inspired the committee of the Society for the Promotion of Female Education in the East ( SPFEE) ) was Maria Newell (later Maria Gutzlaff), whose missionary work was sponsored by Mary Ann Aldersey, and who taught at the Malacca Free School in the late 1820s. But she learnt very quickly that in Christian missionary circles in the 1820s single women were not wanted.

Miss Newell was born in Stepney in August 1794. British Christian missions have always been predominantly the preserve of the middle classes so it was a surprise to see that someone from London’s “East End” had applied to join what was then the all-male London Missionary Society (LMS). When the LMS was founded in 1795 the call went out only for men who were prepared to be the “heroes of the Church”. It did accept that the men recruited as missionaries could take their wives and, by 1812, that women could play an important role in raising funds to support its missionaries. Most of the major Christian missions would not begin recruiting large numbers of single women until the 1890s and certainly not from the East End of London.

But at the beginning of the 19th century Stepney had not yet become a notoriously overcrowded working class area of London. It was still the retreat of mariners and merchants like Miss Newell’s father who was a tallow chandler. It was in Stepney that she was introduced to the faith of the independent-minded dissenters and non conformists to whom the Bible was their guidebook.

She attended the Congregational chapel led by the Rev Andrew Reed, a hymn writer, philanthropist and social reformer. So she probably grew up in an environment where a basic education was viewed as vital for each individual, male and female, if they were to achieve their full God-given potential. She became a school teacher in Blackheath, South London, but it was the Rev Reed who provided her with a reference when she applied to the London Missionary Society (LMS) in early 1826.

She would never have been considered by the LMS if it hadn’t been for its most famous missionary, Dr Robert Morrison championing the cause of single women and the fundraising by some very determined ladies in England. One of those was Mary Ann Aldersey who was single and had the financial means but whose father refused to give his permission for her to answer her call to work overseas. Like Jemima Poppy Miss Newell’s parents were dead and so she was free to make her own choices.

The LMS had originally intended to send two single women to work in association with its Anglo-Chinese College in Melaka (Malacca). But in January 1827 the LMS Examination Committee reported that the health of Miss F Nichols had “considerably failed in consequence of her application to the Chinese language” and it was felt inexpedient to send her overseas.

So Miss Newell travelled with the newly-married Rev Samuel Dyer and his wife, Maria. After months of seasickness and living in a damp cabin Miss Newell was so glad to reach Penang where they met other LMS missionaries, including the Rev Thomas Beighton and his wife, Abigail. It was there that the two Maria’s could see for themselves the successes and failures of trying to run schools for girls among the Chinese and Malay population.

Mrs Beighton and another mission wife, Joanna Ince, had started a boarding school for young ladies advertising that it would have a strict regard to morals, as well as a kind attention to the health and progress of the pupils. Their school brought in sufficient money to make the lives of the missionaries a lot more comfortable in Penang – but the LMS directors in London did not approve. The response from Penang was that if the LMS directors did not recognise the women as missionaries their husbands couldn’t see why they should abide by mission rules!

The Dyers decided that they would stay in Penang rather than travelling on to Melaka, and Mrs Beighton insisted on escorting Miss Newell when she continued her journey. As the tall, masted ship dropped anchor about two miles from the shore at Melaka Miss Newell could see the European settlement on the western side of the estuary with its tree-lined streets which had been laid out by the Dutch and the ruined hill-top church of St Paul’s. To the east were the more closely packed local buildings and beyond them the Malay villages among the green paddy fields and coconut plantations. And then there was the jungle stretching far into the distance to the rugged Mt Ophir. They disembarked into a smaller boat to reach the beach where Miss Newell’s day of heartbreak began.

A missionary was there to greet and provide accommodation for the Dyers. But no-one had come from the missionary community to welcome her. Mrs Beighton, however, had informed the British Resident, Samuel Garling, about their arrival and he had sent a messenger inviting her and Mrs Beighton to his home. The Dutch had, in a treaty in 1825, handed over Melaka to the English East India Company and Mr Garling was the company’s senior representative. Of her arrival at his home Miss Newell wrote: “I was received by him with all hospitality, politeness and dignity of an elegant English gentleman.”

She hadn’t been there long when she received what she described as a cold, rough and unfeeling note from David Collie, the principal of the Anglo-Chinese College, stating she could not stay at his home as he and his wife were already providing accommodation for Dr Morrison’s son and daughter. Miss Newell wept which upset Mrs Beighton. In his letter Mr Collie had informed her that she could stay with Samuel Kidd and his family at the college but when they visited that home they found that the wife was ill and there was just one small room to spare. “It was evidently inconvenient,” commented Miss Newell. Kidd told the LMS directors later that only a woman of fastidious delicacy would have taken offence at being offered a room in his house. And how could they match what Garling had offered?

On her first day in Melaka Miss Newell visited Mr Collie who said little but did inform her that all her study of the Chinese language was useless as most of the local people spoke Malay. “My heart was ready to break,” she wrote.

The missionary community in Melaka was obviously not ready for an independent, single woman. Most mission agencies for years to come would only accept single women who were either the siblings or daughters of male missionaries, or widows who remained on the mission field after their husbands died. What appeared to be a lack of communications between the London directors and the college did not help Miss Newell either. Collie informed her that if she did not follow instructions from the college she would not receive any financial support. The missionaries were even more upset when she took Garling’s advice and accompanied his wife on a trip to Singapore for which he paid all the expenses. It was in Singapore that other missionaries told her to keep her distance from the Anglo-Chinese College. Of those at the college in Melaka she wrote:

“I have been as friendly as I can, but I cannot crouch to them or anyone. It is better to hurt in the Lord than put confidence in man. Debt to me in any circumstances is a wretched thing but in this case necessary. I am now without money but not without faith. Think of me as happy. God will not suffer me to want. He has already done wonders in providing such friends as the Garlings, so high in station yet so pious and ready to help in every good work.”

The Melaka missionaries were far from impressed. Kidd wrote to the LMS directors: “She engaged herself on a tour of pleasure in Singapore, on which she was absent from her station for two months, all without asking a word of advice from us.”

Miss Newell accepted Garling’s offer to work in the girls’ section of the Malacca Free School and began teaching English to those of Portugese and Dutch parentage. An agreement was reached with Collie that she should receive the £200 a year allotted to a single missionary but would give any profits from her school work to the LMS. By staying with the Garlings all her board and lodging costs were covered. She wrote to Miss Aldersey: “It is here a day of small things so far as female education is concerned.”

Miss Newell had seen herself as going out as a missionary and not as a teacher. Instead she found herself teaching in a school where the Lancastrian monitoring system was used – and for which she had no training. Miss Aldersey set herself the task of finding another single woman who would be a companion to Miss Newell and help in the school work. A visit to Edinburgh led to her recruiting Mary Christie Wallace. Miss Wallace reached Melaka in May 1829 but had little time to work with Miss Newell for in November the latter married Charles (Karl) Gutzlaff .

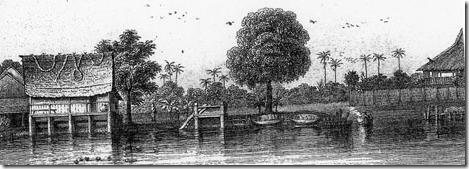

Her husband was a short, squat man from Prussian Pomerania (now in Germany). He was born in 1803 into a tailor’s family in Pyritz and used his considerable talents to gain a place at a school for missionaries in Berlin. He later studied at Rotterdam and was initially sent by the Netherlands Missionary Society to Thailand (then known as Siam). He worked there from 1828 to 1829 with an LMS missionary where the only other foreigners were two Roman Catholic bishops and a Portugese merchant. In February 1830 he took his wife to the small house (below) he had managed to rent by the river in Bangkok. There he had set up a small dispensary as well as distributing Christian booklets.

She wrote to the Garlings:”I have sometimes felt as if buried alive, yet we are very busy. Charles has again fully revised the whole of the Siamese New Testament and is now revising those books of the old which are translated. The whole of the New Testament is translated into Siamese… The sick still throng our doors, the books meet with almost universally delighted reception, our stock is coming down fast, large as it was. Our poor hovel is a great change after the comforts to which I have been accustomed, but God is all sufficient. I am his (her husband’s) humble servant for it is in the assistance I can yield him I hope to be most useful. I have been hither and thither among the miserable and the dirty – to the wretched palaces of the two Cambodian princes, and into their more miserable harems. I have been almost suffocated by crowds of citizens whose curiosity far exceeded their politeness. Everywhere I go a tolerably sized and sometimes very large congregation assembles, and if into a temple, the rush is greater still.”

She commented that the local rulers feared them because of their ability to speak so many languages. It was in Bangkok that Gutzlaff learnt the Chinese Fukhien dialect from the many Chinese living and working there. Later that year the Gutzlaff’s little house was almost engulfed in flames. The noise of the fire woke them up at midnight and it looked as if the whole city was on fire. When the wind blew strongly towards them they prepared to flee and lose everything. “The wind continued unabated; and it appears to me like a miracle, that although the sparks from the immense masses of burning houses were flying around us in every direction, not one fell upon our hut.”

Just a few months later, in February 1831, she died after giving birth to twins of whom one died immediately and the other four months later. Gutzlaff wrote: “The Chinese mission has lost a most industrious and ingenuous labourer, who would have lent effective assistance to the great cause.” He spoke highly of her translation work and what she had done on preparing a Chinese English dictionary. He was very ill himself after her death but was persuaded by the master of a Chinese junk to set sail for China leaving his daughter in the care of a foreign family.

Later he would marry Mary Wanstall who had been running some girls’ schools in Melaka and they set up home in Macau, then a Portugese enclave and, until 1841, the only place where foreigners could settle and build homes in China.

The LMS did not recruit another single woman to send overseas until 1864.

copyright Pip Land January 2012

Sources:

In its first leaflet the SPFEE stated in 1834: “What female superintendents of schools have those (Missionary) societies sent out? Miss Newell… whom the London Missionary Society sent to Malacca in 1827, is a solitary instance. Miss Wallace was adopted by the London Missionary Society, but she was sent out by a few friends. Miss Cooke came into alliance with the Church Missionary Society, but she was sent out by the British and Foreign School Society.”

Stepney: Bridget Cherry, Charles O’Brien & Nikolaus Pevsner, London 5:East, Yale University Press, 2005, p444 (available on Google Books)

E Aldersey White, A Woman Pioneer in China, the Life of Mary Ann Aldersey, The Livingstone Press, London, 1932, pp11-12

Richard Lovett, The History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895, Henry Frownde, London 1899

John Cameron Our Tropical Possessions in Malayan India, Smith, Elder & Co, 1865.

Council for World Mission/London Missionary Society archives at the School of Oriental and African Studies Library, London, including Incoming letters – CWM Ultra Ganges Malacca (from Newell, S Kidd and J Ince) and in CWM S.China Box 3 (from Gutzlaff following his wife’s death).

Gutzlaff’s departure from Thailand and death of his infant daughter: Karl F A (Charles) Gutzlaff Journal of Three Voyages along the coast of China http://www.lib.nus.edu.sg/digital/3voyage.html) pp103-107

Ricci Roundtable: http://ricci.rt.usfca.edu/biography/view.aspx?biographyID=1562 (compiler R G Tiedemann )